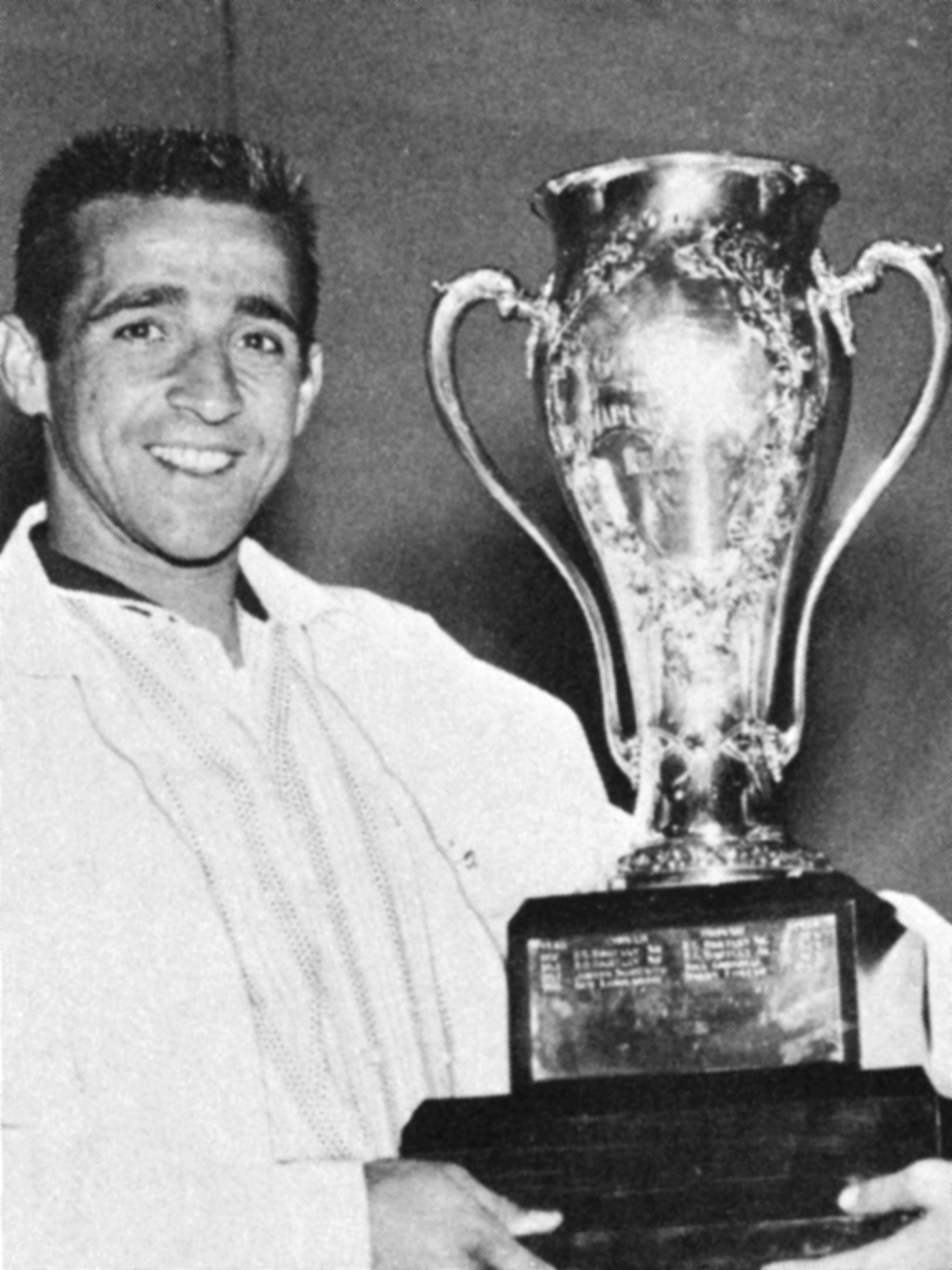

Jack Regas

The Jack Regas Story

Most Unlimited hydroplane drivers start in the Limited classes and work their way up. Jack Regas started at the very top.

The Livermore, California, resident was an employee of Kaiser Industries in the 1950s and worked as a welder. His bosses--Henry and Edgar Kaiser--dabbled in race boats as a hobby.

In 1954, the Kaisers acquired a hydroplane named Scooter (U-12), a product of the famed Ventnor Boat Works of Ventnor, New Jersey. Originally powered by twin Cadillac engines, Henry and Edgar converted it to a single Allison. Regas was a part of the mechanical crew that effected the change.

Scooter measured 25 feet in length with the cockpit located approximately amidships, ahead of the engine well. Scooter was essentially a pleasure boat that met the minimum requirements for Unlimited competition.

As mentioned earlier, Jack had no previous racing experience prior to being named the Scooter's driver. But within a few years, Regas would emerge as one of the most successful pilots in Unlimited history as driver of Edgar Kaiser's Hawaii Kai III. He was the only driver in the decade of the 1950s to win 45% of his races.

The first race for Regas and Scooter was the Lake Tahoe Yacht Club Regatta on July 26, 1954. The Unlimited contest for the Lake Tahoe Championship consisted of one heat of three laps on a 1.67-mile course. The pit area was located at Chamber's Lodge near Tahoe City, California.

Together with Seattle's Lake Washington, Lake Tahoe was the only Unlimited venue west of the Mississippi River at the time.

The reigning king of Lake Tahoe speedboating in the early 1950s was R. Stanley Dollar, heir to the Dollar Steamship Line and owner/driver of Short Snorter, a 1939 Ventnor creation, which had won the APBA Gold Cup in 1947 as Miss Peps V.

Dollar had been racing hydroplanes for two decades. He had raced Limiteds in Europe prior to World War II. Stan won the 1949 Harmsworth International Trophy with Skip-A-Long, the 1952 APBA Gold Cup with Slo-mo-shun IV, and the 1953 Lake Tahoe Mapes Trophy with Short Snorter, all with Allison power.

Despite the inexperience of her driver, Scooter romped to an impressive victory over Short Snorter in the LTYC Regatta. The rookie Regas beat the veteran Dollar over the finish line by 3.1 seconds, 56.479 miles per hour to 55.939. Galloping Gael, a 7-Litre Class hydro, piloted by Roger Murphy, finished a distant third.

The performance of Jack Regas in the Lake Tahoe Championship justified the faith of Edgar Kaiser who had given Jack the job after watching him handle the boat incredibly well in a test run on a flooded gravel pit at the Kaiser Industries plant in Oakland, California. Clearly, this fellow would be heard from in the future. And he was.

Two months later, on September 11-12, Scooter entered its one and only APBA National High Points race--the Lake Tahoe Mapes Trophy--and won that one, too.

This time, the Kaisers and Regas faced a full fleet of local Unlimiteds, including Dollar in Short Snorter, Jay Murphy in Breathless, and Bill Stead in Hurricane IV. A couple of local Limiteds--the 7-Litre California Kid with George Mattucci and Ruthless II with Ken St. Oegger--rounded out the field.

The 1954 Mapes Trophy (also billed as the "Lake Tahoe Mile High Gold Cup" but with no connection to the APBA Gold Cup) was the first Unlimited race in the southwestern United States to count for National Points. The event was co-sponsored by the Lake Tahoe-Sierra Chamber of Commerce and the Mapes Hotel and conducted at the south end of the lake.

Three heats of 15 miles in length were run on a 3-mile triangular course. And three different boats won them. The defending champion Short Snorter captured Heat One, Scooter Heat Two, and Hurricane IV Heat Three.

Scooter ran second, first, and second and posted the fastest lap of the race at 88.748 miles per hour. Hurricane IV finished third, second, and first in her heats. Short Snorter ran the fastest heat of the weekend at 80.631 in Heat One, finished second to Scooter in Heat Two, and then was unable to start in Heat Three.

The top three point-getters were Scooter with 1000, Hurricane IV with 925, and Short Snorter with 625. Then came California Kid with 338, Breathless with 225, and Ruthless II with 127.

Scooter's greatest success was also her swansong. Henry Kaiser retired her on the spot and announced in the pit area that he would build a new Scooter Too for Regas to drive in 1955. Scooter (U-12) faded into obscurity.

A glorified pleasure boat, the U-12 obviously lacked speed and would have been thoroughly outclassed in a race with Slo-mo-shun IV, Miss Thriftway, Gale V, Miss Pepsi, Miss U.S., or Tempo VII. And even in her day, 25 feet was considered rather short for an Allison-powered craft.

Scooter Too (U-10) would be a Slo-mo-style hull, equipped with a more-powerful W-24 rather than a V-12 Allison engine. But unlike her predecessor, the Too never won a race and was sidelined by mechanical breakdowns in all five of the regattas that Jack entered with it.

On a historical note, Scooter (U-12) was the only forward-cockpit (or cabover) boat to win an Unlimited race in the decade of the 1950s. Not until Gene Whipp captured the 1973 President's Cup with Lincoln Thrift's 7-1/4% Special would another Unlimited winner steer from the front.

And not until Whipp in 1973 would another rookie driver duplicate Jack Regas's performance of winning his first-ever Unlimited race.

Jack's first ride in the incomparable "Pink Lady" Hawaii Kai III came at the 1956 Seafair Trophy Race in the Second Heat after Scooter Too had sunk in the First.

Hawaii Kai III (U-8) was the finest competitive machine in the history of Unlimited hydroplane racing at that point in time. The Kai was the epitome of the all-conquering Ted Jones design of the 1950s. The Edgar Kaiser-owned entry set records of speed and endurance that stood for many years.

The Kai was patterned after the Jones-designed Rebel, Suh and was extra long since the Kaiser team felt this would facilitate the setting of straightaway records, and Jones felt that 30 feet--rather than 28 feet--would make a safer hull. The boat turned out to be 1,400 pounds heavier than Rebel, Suh because of some extra heavy wood that was used in construction.

Hawaii Kai III's first appearance in competition was at the 1956 Lake Tahoe Mapes Trophy Regatta. She was a last-minute entry and lacked preparation time. With Howard Gidovlenko driving, the Kai took second place in a four-boat field but was outperformed by her sister ship, the Scooter Too, and also by the victorious Shanty I, owned by Bill Waggoner and driven by Russ Schleeh.

Moving on to Seattle for the Seafair Trophy Race, Hawaii Kai III experienced mechanical difficulty and failed to score any points.

When Gidovlenko--who had failed to start the initial go-round--asked to be relieved of his seat in the Kai, Regas was given the wheel for the second heat. A broken high-tension lead in the magneto halted the boat and her new driver after only a couple of slow laps, but it was the start of one of the most colorful and successful associations in racing history.

Flying the burgee of the Seattle Yacht Club, Hawaii Kai III entered the 1956 Gold Cup race on the Detroit River. Also representing Seattle were Slo-mo-shun IV, Shanty I, Maverick, Miss Seattle and Miss Thriftway. The SYC team had lost the 1955 Gold Cup in Seattle to Joe Schoenith's Gale V, which represented the Detroit Yacht Club.

After suffering extensive hull damage in a pre-race test run on account of propeller failure, the Kai took fifth-place in a 14-boat field and gave national champion Shanty I a good battle in Heat 2-B. The race ultimately went to Miss Thriftway, owned by Willard Rhodes and driven by Bill Muncey. This assured a Gold Cup race on Lake Washington in 1957.

As things developed, another Seattle boat sustained damage in a pre-race accident at the 1956 Gold Cup as well. The "Grand Old Lady" Slo-mo-shun IV was destroyed when it encountered the wake of an illegally moving patrol boat, and crashed, seriously injuring driver Joe Taggart.

The crestfallen Slo-mo IV owner, Stan Sayres, offered the use of his spare Rolls-Royce Merlin engine to the Kai, which had previously used Allison power, and his top-notch volunteer crew to maintain it.

Here was a windfall if ever there was one! This was the same basic group of mechanical wizards that had won five of the previous six Gold Cups with Slo-mo-shun IV and Slo-mo-shun V and had set the then-current mile straightaway record for propeller-driven boats at 178.497 miles an hour in 1952 with Slo-mo IV. This team consisted of crew chief L.N. (Mike) Welsch, Wes Kiesling, George McKernan, Rod Fellers, Elmer Linenschmidt, Fred Hearing, Pete Bertellotti, Bob Stubbs, Don Ibsen, Jr. and Jack Watts.

Starting with the 1956 President's Cup in Washington DC, the entire Slo-mo organization--with the exception of Taggart--transferred its affiliation to Hawaii Kai III, which in essence became "Slo-mo-shun VI" in the minds of countless Seattle fans.

With Jack Regas continuing as driver, the Kai finished third in the President's Cup with a victory in Heat 2-B. Wrong selection of a propeller was blamed for the boat's inability to place higher.

A second Unlimited contest for the Rogers Memorial Trophy, designated as the American Speedboat Championship race, also was contested at the '56 President's Cup Regatta. Equipped with a new, smaller propeller, Regas charged to victory in both heats, beating the favored Shanty I and shattering all records for the event. Hawaii Kai III's best heat speed of 103.487 was only one mile an hour off the world record of 104.775 for the 15-mile distance, set in 1955 at Elizabeth City, North Carolina, by Danny Foster in Tempo VII.

The Rogers Memorial was the first of ten first-place trophies that the "Pink Lady" would win during her career and also the first indication of her high-speed potential.

The craft continued its winning ways at the season finale in Las Vegas for the Sahara Cup on Lake Mead. Regas scored victories in all three heats, after Shanty I went dead in the water while leading in the final. The Kai, nevertheless, turned the fastest lap, heat, and race averages of the regatta.

Hawaii Kai III's late-season brilliance vaulted her to second place behind Shanty I in a field of 31 boats in the 1956 National High Point Championship Series, although this accomplishment was scarcely recognized at the time. This was on account of the High Point Championship not being accorded the prestige that it enjoys today. On the contrary, these were the days when the Gold Cup reigned supreme as the one prize that outweighed all others in terms of sentiment and pride of possession.

During the winter of 1956-57, Edgar Kaiser announced that, due to business pressure, he would have to retire as an active Unlimited hydroplane owner. However, in recognition of the crew in making the boat a frontrunner, Kaiser gave the Kai to the former Slo-mo team for the '57 season. Mike Welsh was designated as the representative owner.

The first three competitive outings of 1957--the Apple Cup, the Mapes Trophy, and the Gold Cup--were all disappointments for the Hawaii Kai team. They established that they had the fastest entry on the circuit but failed to bring in any victories due to an inability to go the 90-mile distance. There was some consolation, however, in that the Kai and Jack Regas won every heat they finished and set at least one course record in every event.

In the Apple Cup at Lake Chelan, Washington, Hawaii Kai III set a world competition lap record of 116.004 on a 3-mile course. The previous best had been Tempo VII's 106.007 at Madison, Indiana, in 1955. The Kai’s mark would stand until 1963. A case could be made for Hawaii Kai III being the most significant record-breaking boat of the post-World War II era. This is because it raised the competition lap record by more miles an hour and held it longer than any other craft.

Also at Chelan, the Kai did five laps at approximately 110.4 miles an hour in a ten-lap heat. This unofficially bettered the previous 15-mile competitive standard by almost six miles an hour.

Still, a race boat must be durable as well as fast. So, victory went to Bill Waggoner's Maverick, driven by Bill Stead, at the Apple Cup. Bill Boeing's Miss Wahoo, driven by Mira Slovak, won the Mapes Trophy. And Miss Thriftway's Bill Muncey once again did the honors at the Gold Cup, returning the "Golden Goblet" to the trophy shelf of the Seattle Yacht Club for yet another year.

The Kai, however, turned the fastest 30-mile heat on a 3-mile course in the history of Unlimited racing with a record speed of 109.823 in Gold Cup Heat 1-C. This performance erased the previous high of 108.717 set by Miss Wahoo in Heat 1-A of the same event.

There is a tide in the affairs of boat racing, and Hawaii Kai III's tide was about to come in. Unlike her previous races of 1957, which were 90 miles in length, all of the remaining contests were 45 miles or less.

On August 31, 1957, one year almost to the day that the Kai, Regas, and the Slo-mo crew joined in partnership, the "Pink Lady" scored an impressive victory over 15 other boats in the Silver Cup Regatta on the Detroit River.

After finishing second to Miss Wahoo due to engine trouble in the initial go-round, Hawaii Kai III won the next two heats. The Gold Cup champion Miss Thriftway was fairly and squarely beaten in the finale, 104.161 to 101.199.

The President's Cup, three weeks later, was another classic. The Kai won all three heats and was clearly the class of the 15-boat field.

On the same weekend, the "Pink Lady" proceeded to win her second straight Rogers Memorial Trophy (in spite of jumping the gun in the final heat) and was simply overwhelming. Moving on to Madison, Indiana, for the Governor's Cup on the Ohio River, Hawaii Kai III made it four in a row, winning another three-heat grand slam. The Kai also clinched the 1957 National High Point title by a wide margin at Madison.

In the last race of the season, Hawaii Kai III bowed out in style, retaining her Sahara Cup title while placing first, first and second in heat action. The Kai needed only to finish the last heat to win the race on points. Jack Regas nevertheless staged a thrilling down-to-the-wire duel with Brien Wygle and Thriftway, Too in the final stanza, which was run on rough water and in almost total darkness!

As if all of this wasn't enough, Hawaii Kai III then became the fastest propeller-driven boat in the world. On November 29-30, 1957, the Kai raised the mile straightaway record by nine miles an hour to 187.627, a mark which would stand until 1960. The "Pink Lady" also raised the world kilometer record by ten miles per hour to 195.329, a mark which would stand until 1962.

According to the American Power Boat Association rules, a straightaway record is determined by the average of two runs in opposite directions over the same certified course.

During the time trials off Sand Point, in Seattle on Lake Washington, the Kai made one pass through the kilometer trap at 199.726 miles an hour. The boat's raw time for this run was 11.162 seconds, which under APBA rules was rounded off to 11.2 seconds for the 199 mph clocking. If the raw time had been used, the speed would have been 200.409 instead. Thus, Hawaii Kai III was the first propeller-driven craft to turn an "official" 200 miles an hour.

With five straight race wins, the High Point Championship, and a host of speed records to her credit, the Kai stood at the very top of the racing world. She was the logical choice for the cherished number one spot on Yachting Magazine's 1957 Motor Boat All-American Racing Team.

But one important accolade was still missing. One more element was still needed to make the team's triumph complete. The "Pink Lady" had still not won the Gold Cup.

The year of 1958 dawned with the status of Hawaii Kai III uncertain. It was unknown whether Edgar Kaiser would campaign the boat one more year. While the other Unlimited hydroplane teams prepared for the upcoming season, the defending National Champion languished in drydock, unattended.

In June, Kaiser announced that the Kai would not race again under his ownership and was available for sale. One of the primary reasons for this was the lack of time to properly pursue the sport by both Kaiser and the crew.

But as Gold Cup time neared, there were those who still hoped that Kaiser, Regas, the crew, and the Kai would come back for one more curtain call. And they did.

Just two days before the July 31 deadline for filing Gold Cup entries, the APBA office in Detroit received a phone call from the Kaiser camp that put Hawaii Kai III back on the active list of Unlimited hydroplanes.

This move was to guarantee any last-minute buyer of the boat a place in the August 10 race, Kaiser explained. It was not until the afternoon of August 1 that he finally agreed to send the Kai to the starting line one more time under his ownership.

The crew quickly reassembled. Their main concern at the outset of the race was the APBA rule which forbade engine changes between heats of an Unlimited race, although component parts (such as spark plugs) could be changed.

If the Rolls power plant had an Achilles heel, it was the quill shaft, which drove the supercharger impeller. In the past, more than one boat had been beached for the day when the quill shaft had twisted or been broken in the heat of competition.

Solving this problem was crucial to Hawaii Kai III's chances since the craft had not finished a 90-mile race since before it was a contender.

Edgar Kaiser had an idea. Why not change the quill shaft between heats? Such a difficult task had never been attempted, but the crew agreed that it was worth a try.

The first practice attempt took 46 minutes, which would have been too long for the boat to be back in the race. But after additional practice, the crew was able to do it in 26 minutes.

Jack Regas, who had not settled himself into a hydroplane cockpit since the record run in November, lacked the sharpening of a recent race competition. While the other top drivers had all seen previous 1958 action, Regas had only a few days to regain his 1957 form for the most important race of the year.

In Jack's words, "I knew I had to beat Bill Stead." This was a correct assumption. The Reno, Nevada, cattle rancher was coming off back-to-back wins in his two previous races with Maverick, the former Rebel, Suh, which ironically was the boat after which Hawaii Kai III had been patterned.

In previous seasons, the Bill Waggoner-owned entry had affiliated with the Seattle Yacht Club. But Waggoner had recently transferred his loyalty to the Lake Mead Yacht Club of Las Vegas, Nevada. For Seattleites, Maverick was now in the enemy camp.

On the first day of qualifying, Stead turned a record lap of 120.267 and a record three-lap average of 119.956. This indicated that Maverick was apparently three miles an hour faster than the previous year. This was considered significant since the best that the "Pink Lady" would do was 119 before going dead in the water.

In addition to the Kai and the Maverick, much pre-race speculation focused on the Miss Thriftway, the Miss Bardahl and the Miss U.S. I. But the drivers of these boats--Bill Muncey, Mira Slovak, and Fred Alter--simply lacked the speed that Regas and Stead enjoyed.

Race day dawned bright and warm. The water was calm and ideal for competition. Hawaii Kai III and Maverick found themselves drawn into Heat 1-A.

The Kai crossed the starting line first, just ahead of Miss Bardahl with Maverick a close third. Stead powered past Slovak and took off after Regas. Maverick tried but could not keep up with Hawaii Kai III. Regas ran the first five laps of this ten-lap heat at approximately 112.8 miles an hour (compared to the world mark of 112.312 for the 15-mile distance, set by the first Miss Thriftway at Madison in 1957). Jack then backed off to a more conservative pace for laps six through ten, as per instructions from his crew, and took the checkered flag 22 seconds ahead of Maverick for an average of 108.734.

No one could deny that the "Pink Lady" was back and stronger than ever. Her historic performance of 112.8 for the first five laps of Heat 1-A would stand unchallenged until 1964.

While the Kai crew prepared for the next set of preliminaries, Heat 1-B produced a surprise victory by longshot Miss Pay ‘N Save. Driver Al Benson's average speed, however, was only 93.701.

The new and improving Miss Thriftway won Heat 1-C quite handily. The defending champion Bill Muncey was fast--at 108.259--but not as fast as Hawaii Kai III. Muncey, unfortunately, was unable to capitalize upon his solid 1-C performance.

At the start of Heat 2-A, Miss Thriftway lost its rudder and crashed into a 40-foot Coast Guard patrol boat. Muncey, who had jumped from the cockpit at the last instant, was pronounced "dead" when a rescue worker could find no pulse. Bill revived, however, to race again.

But as far as the 1958 Gold Cup was concerned, Seattle's chances were not good. The other six local boats were either out of the race or were too far behind in both speed and points. With two 30-mile heats left to run, Hawaii Kai III was the only hope.

The re-run of Heat 2-A was surprisingly won by Coral Reef, a perennial tailender from Tacoma, Washington, which had come alive and averaged a respectable 101.237 for the ten laps.

Maverick led at the start of Heat 2-B and through the first turn. As they entered the first backstretch, Jack Regas made his bid and thundered past Bill Stead to take over first place. Maverick fought gamely but couldn't catch Hawaii Kai III. Regas maintained a lead varying from 100 yards to a quarter of a mile with Stead charging after him, many times airborne, in the Kai's wake. Then, on the final backstretch, Maverick slowed so that the "Pink Lady's" winning margin was stretched to a full mile.

The Las Vegas challenger had been decisively beaten. Stead now trailed Regas, 600 points to 800, and by almost a minute in total elapsed time. The Maverick driver sheepishly conceded, "I had forgotten how fast the Kai could go."

In addition to averaging 106.299 for its second 30-mile heat, Hawaii Kai III had done approximately 108.5 miles an hour for the first 45 miles of the race. This unofficially raised the Kai's own record of 106.061 for that distance, set in 1957 at Madison. The mark would stand until 1962.

As the shadows lengthened on that storied Gold Cup afternoon, the seven finalists took to the water for the last time. But one of them never left the dock. Maverick had broken a spline coupling in its twin-stage Allison engine, and the crew couldn't replace it in time. There would be no victory celebration for the Bill Waggoner camp on this day.

Hawaii Kai III exited the first turn of the Final Heat in first place and went on to win, hands down. Coral Reef pilot Harry Reeves tried desperately to catch Jack Regas but to no avail. Every time that Reeves made a bid, Regas punched his throttle and sprinted ahead out of reach, maintaining his safe lead.

The Rolls-Royce Merlin engine, prepared so meticulously by the Slo-mo crew, was performing perfectly, as the partisan Seattle crowd cheered the "Pink Lady" on to the checkered flag.

The Gold Cup was safe for another year! The Kai had done it! Even after many months on the shelf, the Edgar Kaiser craft had demonstrated its complete mastery over the rest of the fleet.

Hawaii Kai III had finished the 90 miles, which the critics had predicted she could not do, and done so at a record-breaking 103.481 mph, beating Miss Thriftway’s 1957 mark of 101.979.

The Kai had become the first Unlimited hydroplane to win six consecutive races. This also was the first time that a thunderboat had completed 300 consecutive miles at a winning pace. The previous mark was the Skip-A-Long's 299.3 miles at a winning pace in 1949. The record would stand until 1962.

A jubilant Edgar Kaiser, the Slo-mo crew, and Jack Regas were the heroes of the day. Their triumph was now complete. There were no more worlds to conquer.

Now the team could disband with a clear conscience. And they did...within a matter of days. The 1958 Gold Cup was their last race together. There would be no encore.

With the demise of the Kaiser team, Regas found himself without a ride. But not for long. For 1959, Jack signed on as helmsman for Ole Bardahl's "Green Dragon" Miss Bardahl, which had won the National High Point Championship in 1958 with Mira Slovak and Norm Evans as drivers.

George McKernan--another Hawaii Kai alumnus--accompanied Jack to the Miss Bardahl (U-40) organization as crew chief.

Jack probably would have won the 1959 Apple Cup if high winds hadn't forced cancellation of the Final Heat. The victory went instead to Chuck Hickling and the Miss Pay ‘N Save on the basis of total accumulated points. The "Green Dragon" nevertheless turned the fastest 15-mile heat (107.526) and 3-mile lap (112.266) of the race.

Regas and Miss Bardahl won the first two heats of the Detroit Memorial Regatta in fine fashion but failed to finish the finale. The Bardahl team at least had the satisfaction of defeating the overall winners, Bob Hayward and Miss Supertest III, by a wide margin in Heat 2-B.

The Miss Bardahl's promising season was tragically derailed at the Diamond Cup in Coeur d'Alene, Idaho. Regas and the U-40 waged a brilliant side-by-side battle with Bill Muncey and Miss Thriftway in Heat 1-A, with Muncey winning it, 104.895 to 104.813. Regas was running third in Heat 2-A when he encountered the wake of another boat and was knocked unconscious.

Jack suffered a skull fracture and was hospitalized in critical condition. He languished in a coma for nearly a month. Ole Bardahl was grief-stricken and announced his retirement from racing.

While Regas was fighting for his life in a local hospital, the 1959 Seattle Gold Cup was run without an entry from the Miss Bardahl team.

Jack eventually recovered and even showed up as a spectator at the Reno Regatta in late-season. But he did not drive in competition again for eight years.

Bardahl reconsidered his retirement and the U-40 returned to action, six weeks after the accident, with Bill Brow in the cockpit.

The years between 1960 and 1967 were difficult ones for Regas. He still had a burning desire to compete. But the seriousness of his Coeur d'Alene injury worried people--despite the clean bill of health attested by Jack's doctor.

Finally, in mid-season 1967, opportunity knocked. On the recommendation of Mike Welsch, Regas was hired to drive for Notre Dame, starting with the Madison Regatta.

His comeback boat was a new Les Staudacher hull. In its two previous races with rookie Jim McCormick as pilot, Notre Dame was terribly erratic. Unlimited Commissioner J. Lee Schoenith threatened to ban it from competition. Extensive pre-season testing did little to alleviate the extremely unfavorable handling characteristics. Designer/builder Staudacher was called in to lend a hand and was quite frankly baffled over the boat’s inability to perform.

At the third race of the season in Madison, Regas replaced McCormick in the Notre Dame cockpit. It was thought that Regas, being a veteran, could better help the crew in dealing with the boat’s rough riding tendencies.

The 1967 Notre Dame may or may not have been able to develop into a viable contender. The boat was involved in an accident at the start of the Gold Cup Race in Seattle and was destroyed.

Moments before the one-minute gun, prior to Heat 1-A, another boat was late in starting and left a side-ways wake, perpendicular to the race course. Sixty seconds later, the front-running Notre Dame fell into that wake, ripped off a sponson, and ricocheted directly in front of Chuck Hickling, who was driving Harrah’s Club.

The two behemoths crashed into each other at terrific speed and sank to the bottom of Lake Washington. Thankfully, both Hickling and Regas escaped serious injury and quickly recovered. Although their boats were less fortunate.

When it was determined that repair of the damaged Notre Dame hull was impossible, the team retired to await delivery of a new boat for 1968.

This latest Notre Dame was a Jon Staudacher design. Jon, son of Les, had previously assisted his father in the boat building business. But this was Jon’s first solo effort in the Unlimited Class.

The overall configuration followed the low-profile trend and featured a snub-nosed bow. Jack Regas returned as the driver.

Truth to tell, the 1968 Notre Dame wasn’t much of an improvement over her 1967 counterpart. The new boat was fast on the straightaways, but kept wanting to swap ends in the turns. (Jon Staudacher’s next Unlimited, the 1975 Atlas Van Lines, had the same problem.)

As erratic as the 1968 hull was, no one could deny her competitiveness. At each of the first four races of the season, Regas had her in the thick of things and scored at least one heat victory at every event. The boat’s best performance occurred on the Ohio River at Madison, Indiana.

In Heat 2-C at Madison, Regas convincingly beat the National Championship team of Billy Schumacher and the Miss Bardahl. Jack also outran the formidable combination of Bill Sterett and the Miss Budweiser. Notre Dame set a course record of 104.026 for the 15-mile distance that stood for five years. Then, in the Final Heat, Notre Dame led for four laps and was two laps from victory when Miss Bardahl finally passed Notre Dame and went on to claim the Governor’s Cup.

The 1968 Madison Regatta is remembered as the race where Notre Dame owner Shirley McDonald came the closest to a third career win. (She had won the 1964 Dixie Cup with Bill Muncey and the 1966 President's Cup with Rex Manchester.) None of the drivers that succeeded Regas were able to duplicate Jack’s effort in this regard.

Midway through the 1968 season, Regas ranked second only to Schumacher in Driver High Points. He had more points than Muncey of Miss U.S., Sterett of Miss Budweiser, McCormick of Harrah’s Club, Warner Gardner of Miss Eagle Electric, Tommy Fults of My Gypsy, and Dean Chenoweth of Smirnoff.

But Notre Dame was still a handful to drive. The boat spun out twice at Seattle and pitched Regas into the water on the first lap of the Final Heat. Jack suffered a serious back injury and, on the advice of doctors, retired from racing. Were he to re-injure his back, he could have been crippled for life. It was the end of the line for one of racing’s all-time greats.

Substitute driver Leif Borgersen finished the season but achieved mediocre results. Heat speeds were down about 5 miles per hour. Notre Dame was simply not the contender she had been with Regas driving. With Borgersen, she was strictly an also-ran. And no matter who was driving, she still wanted to swap ends.

At the 1968 San Diego Cup, Borgersen spun the boat and sank it in Heat 1-A. That was the last straw for this particular Notre Dame hull, which was retired and never entered in another race.

His Unlimited career a memory, Jack Regas continued to attend the races as an enthusiastic spectator, never too busy to pose for a photograph or to sign an autograph.

Jack's all-time favorite boat is--and always will be--Hawaii Kai III.

The Kai unfortunately no longer exists. The boat that enjoyed such a dramatic life was given a dramatic "death" in 1972. The Kaiser family gave the "Pink Lady" a Viking funeral at the Kaiser estate on Orcas Island in the state of Washington. The Kai was set ablaze and cut adrift as the sun set on her colorful career.

During the winter of 1990-91, the staff of the Hydroplane and Raceboat Museum in Seattle decided to revive the Hawaii Kai III legacy for a new generation of race fans.

The former Breathless II, built in 1957, was called upon to stand in for the departed "Pink Lady." Breathless II was the perfect choice to wear the Kai's tropical rose and coral mist racing colors. She is a line-for-line hull duplicate of the original Hawaii Kai III, although the sponsons are a bit different. The "Quasi-Kai" is a stunning representation of a racing legend.

At the 1991 Seattle Seafair Regatta, Museum President Dr. Ken Muscatel took the "Quasi-Kai" for a race day morning exhibition run on Lake Washington. Riding in the cockpit with Ken was special guest Jack Regas, the man who saved the Gold Cup for Seattle in 1958 and who occupies a permanent place of honor in the annals of boat racing history.