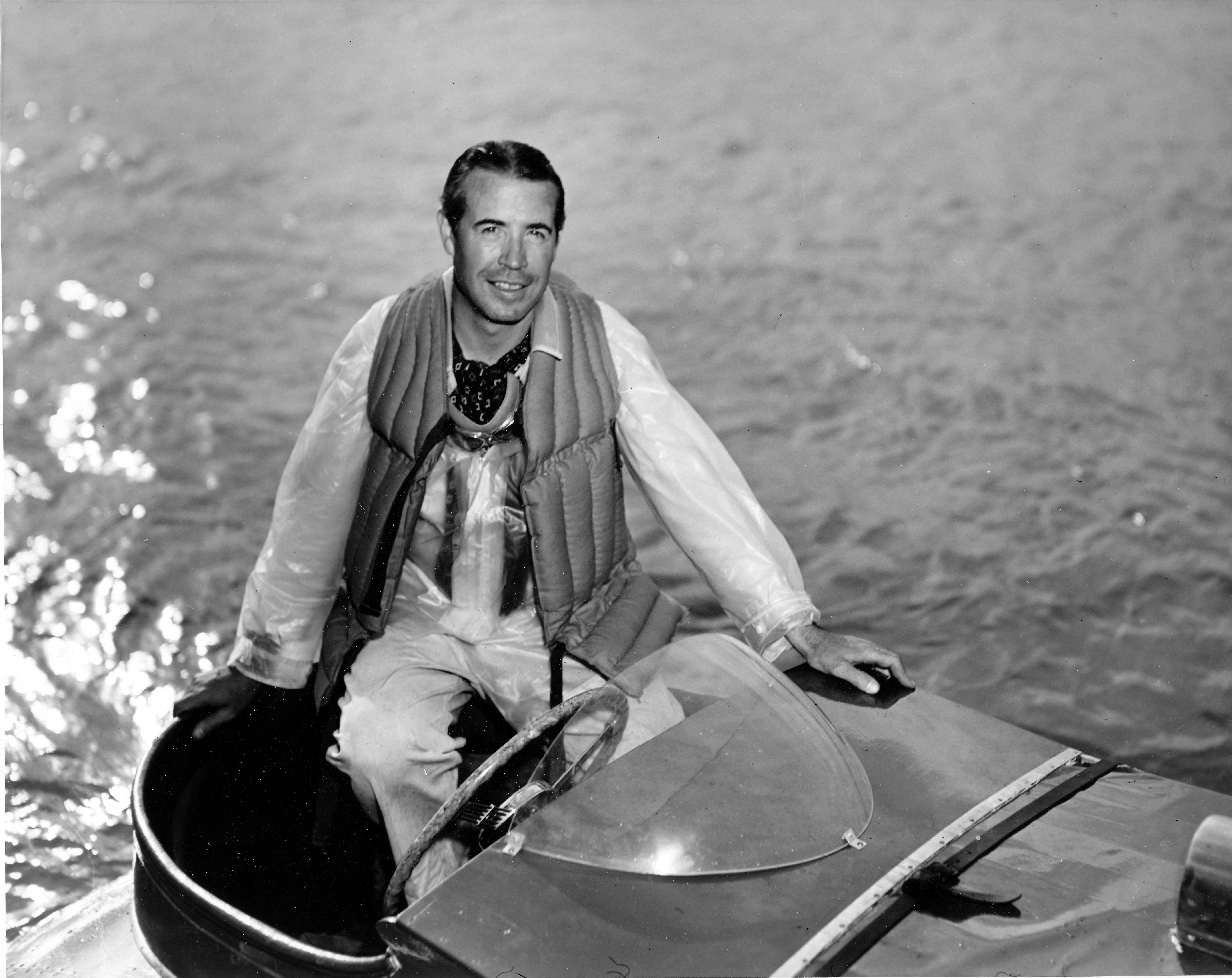

Lou Fageol

The Lou Fageol Story

Major League boat racing can be roughly divided into two categories: pre-World War II and post-World War II. Very few drivers achieved success in both eras. Bill Cantrell and Dan Arena come to mind; so do Harold Wilson and Marion Cooper. There was also Lou Fageol.

Fageol had a distinguished--albeit controversial--driving career that began in 1928 with Outboards and accounted for 74 first-place trophies. Lou’s greatest thrill was his victory in the 1950 Harmsworth International Regatta with Slo-mo-shun IV when he turned the first-ever heat at over 100 miles per hour.

Having been raised in the environs of Oakland, California, Fageol associated himself with the California Gold Cup Class of the 1930s with a series of boats named So-Long.

The premier trophy in the western United States before the war was the Pacific Motor Boat Trophy, which was donated by the magazine of the same name. It had first been offered for competition in 1923. The trophy was intended as a challenge cup to be emblematic of the free-for-all speed boat championship of the Pacific Coast.

Like its eastern counterpart, the APBA Gold Cup, the PMB Trophy was meant to encourage the development of racing boats on the Pacific Coast.

Fageol won the final four pre-war races for the PMB Trophy--in 1939-40-41 with his Gold Cup Class So-Long and in 1942 with his 225 Cubic Inch Class So-Long, Jr.

In 1939, Lou headed east with his Ventnor-built So-Long to challenge the eastern Gold Cup establishment. His boat used half of a 12-cylinder Curtiss Conqueror. The power plant consisted of two banks of three cylinders each, rated at 450 horsepower. The hull was a non-propriding three-point hydroplane and one of the first boats in the world with sponsons on it.

Fageol made a start in the 1939 Gold Cup at Detroit but didn’t make much of an impression. During the warm-up for Heat One, the boat struck some drift and suffered propeller damage. This reduced her to a slow cruising speed. So-Long did, however, complete the ten 3-mile laps in last place behind My Sin, Miss Canada III, and Mercury.

So-Long tried to make a go of it in Heat Two, even though propeller vibration had cremated the boat’s thrust bearing in the initial contest. Fageol was ultimately flagged off the course at the end of lap seven and given a DNF for being too far behind.

This was Lou’s first appearance in a Gold Cup race. It would not be his last.

Not for eight years would So-Long finally come into her own. Renamed Miss Peps V by the Dossin brothers of Detroit, she won the Gold Cup in 1947 with Danny Foster driving and was one of the first boats to try an Allison V-12 aircraft engine in competition.

Lou’s father, Frank Fageol, was the head of the Fageol Twin Coach Company, which manufactured buses. After the war, Lou became President of the company and, together with Dan Arena, started the 7-Litre Class. The engine of choice in the 7-Litre Class was the 404 cubic inch Fageol bus engine.

So-Long, Jr., using a bus engine, was the 7-Litre prototype and won the 1946 Silver Cup at Detroit for boats that didn’t make the cut for the final two heats of the Gold Cup.

Lou originally envisioned the 7-Litres as a sort of “Junior Gold Cup Class” and capable of competing on the same water with Unlimited hydroplanes. This idea was abandoned when it became obvious that a Fageol 404 was no match for a 1710-cubic-inch Allison, even in a stock configuration.

Lou also involved himself in Indy Car racing at this time, but not as a driver. In 1948, his friend “Wild Bill” Cantrell completed 161 laps of the Indianapolis 500 at the wheel of the Fageol Twin Coach Special.

Fageol landed his first Unlimited ride in 1949. From then on, his focus was the Unlimited Class, although Lou continued to field a 7-Litre entry that his son Ray Fageol drove.

Lou’s Unlimited debut was the 1949 Silver Cup at Detroit with Jack Schafer’s Such Crust II, an experimental craft designed by his friend Dan Arena that never quite made the competitive grade. Fageol nevertheless gave it his all and established himself as a “pedal-to-the-metal” competitor in his very first Unlimited appearance.

Fageol deposited riding mechanic Ray Tavenner near the press dock on the fifth lap of the First Heat of the Silver Cup. Lou was apparently driving too fast for his companion.

Later in the season, Fageol transferred to Such Crust I but was no match for the all-conquering combination of Bill Cantrell and My Sweetie, the 1949 National Champions.

Not until 1950 did the racing world stand up and take notice of Lou Fageol. After two decades as a boat racer, Lou established himself as a major new talent on the Unlimited scene.

On two occasions in 1950, Fageol had the opportunity to step into My Sweetie as a relief driver for the injured Cantrell. The first was in Heat Two of the Gold Cup at Detroit. Lou pushed My Sweetie into the lead at the start and stayed there, ahead of Ted Jones and Slo-mo-shun IV, for 9-3/4 laps. Then, with a quarter lap to go, My Sweetie’s Allison engine failed due to low oil pressure, which sidelined the entry for the day.

The following weekend, Fageol helped Cantrell win the Ford Memorial Regatta by driving the Final Heat in My Sweetie.

Later that summer, Stan Sayres selected Lou to drive Slo-mo-shun IV in the Harmsworth Regatta at Detroit when driver/designer Ted Jones was injured. With Fageol at the wheel, Slo-mo became the first craft in history to average 100 miles per hour in a heat of competition around a closed (5-nautical mile) course.

Slo-mo-shun IV averaged 100.680 in the second heat of the best-two-out-of-three-heat series. After nearly a half-century of organized power boat racing, the century mark had at last been conquered. Gar Wood had done it on the straightaway at 102.256 in 1931 with Miss America IX, but this was the first time ever on a closed course.

The “IV” was the first propriding three-pointer to run successfully. Such Crust II had also experimented along those lines.

Crew Chief Mike Welsch was riding mechanic with Lou in the 1950 Harmsworth race. According to Welsch, Fageol drove like a man possessed. Mike did not appreciate the experience of riding with Lou at all.

Two days after the Harmsworth, Fageol and Slo-mo IV continued at their historic pace and scored a decisive victory in the first 10-mile heat of the Silver Cup, which was run on the Harmsworth Trophy course. Lou averaged 104.318 but, in so doing, the intermediate shaft bearing failed and ended Fageol’s chances for a second straight Detroit River triumph.

Lou was now a permanent member of the Seattle-based Slo-mo team. When owner Sayres unveiled a new Slo-mo-shun V in 1951, Fageol was named the driver.

The first West Coast Unlimited hydroplane race to count for APBA National Points was the 1951 Gold Cup on Seattle's Lake Washington. Slo-mo-shun IV had won the 1950 Gold Cup in Detroit and had earned the right to defend her title on home waters, as per the then-current rules.

Slo-mo-shun V emerged victorious in 1951--a contender right out of the box, just as Slo-mo-shun IV had been. Lou had first tried for the Gold Cup in 1939 with So-Long. Now, at long last, he had a victory.

Fageol set a world lap speed record of 108.633 miles per hour on the first lap of the first heat. The race was declared a contest on the basis of two completed 30-mile heats on a 3-mile course, after the fatal accident involving Quicksilver, a step hydroplane from Portland, Oregon.

Quicksilver’s crash occurred on lap-three. Officials started flagging the other boats off of the course. So intense was Lou Fageol’s concentration on the race at hand, he was on his ninth time around before acknowledging the signal to withdraw.

Slo-mo-shun V thoroughly dominated the opposition in the 1951 Gold Cup and was challenged only by Chuck Thompson in the Miss Pepsi.

In winning the 1951 Gold Cup, Lou became but the third competitor in history to capture both of power boat racing’s crown jewels: The Harmsworth Trophy and the Gold Cup. The two previous double champions were Fred Burnham and Gar Wood.

Following the 1951 season, designer Ted Jones left the Slo-mo-shun team. After the split between Jones and Sayres, Slo-mo-shun V was rebuilt by Anchor Jensen. The boat was still fast but experienced handling difficulties and was never quite the same.

Fageol’s next two Gold Cup appearances were problematic.

In the first heat of the 1952 race, Slo-mo-shun V battled head-to-head for five laps with Miss Pepsi, a twin-Allison-powered step hydroplane from Detroit. Never before had two boats averaged over 100 miles per hour for 15 miles. As Fageol crossed the line at the start of lap six, Slo-mo V’s overheated engine block cracked from insufficient cooling water, leaving Miss Pepsi to go on for the win.

Fortunately for the Sayres team, Stan Dollar in Slo-mo-shun IV rebounded to win the next two heats and retain the Gold Cup in Seattle for another year.

When Sayres chose not to race in the East in 1952, Fageol made a non-Slo-mo appearance at the Silver Cup, where he finished second aboard Jack Schafer’s Hornet-Crust with a victory in Heat One.

Lou almost missed the 1953 Gold Cup entirely when Slo-mo-shun V sank and was badly damaged in a test run and couldn’t be repaired in time to compete. Fageol nevertheless had a hand in keeping the Stan Sayres victory string alive. Lou alternated with Joe Taggart in the cockpit of Slo-mo-shun IV. Taggart drove in Heats One and Three; Fageol drove in Heat Two. Together, they won all three heats.

After racing only in Seattle in 1951 and 1952, Sayres sent Slo-mo-shun V on the eastern tour in 1953. The team failed to finish at the Silver Cup in Detroit but became the first West Coast winner of the President’s Cup in Washington, D.C.

The President’s Cup Regatta was a mainstay on the APBA calendar from 1926 to 1977. Only the Gold Cup and the Harmsworth Trophy eclipsed it in terms of prestige.

Fageol and the “V” won the first two 15-mile heats and placed second in Heat Three. Second-place Chuck Thompson and Such Crust III ran fourth, third, and first. Thompson averaged 93.918 in the finale to Fageol’s 92.737 on a 3-mile course.

This marked the first time in Potomac River history that two boats had averaged better than 90 miles per hour on that turbulent body of water. Be that as it may, Lou sought to have the Such Crust III pilot disqualified for allegedly cutting in front of and illegally watering down Slo-mo-shun V. But Fageol’s protest was eventually disallowed, after a Detroit-dominated APBA fact-finding committee ruled that no foul had occurred.

The victorious Slo-mo driver claimed another first-place award at the President’s Cup Regatta when So-Long won both heats of the 7-Litre Class race with Ray Fageol driving.

But Slo-mo-shun V was still a handful to drive. Two years earlier, Lou had described it as the best handling boat that he had ever driven. But the “V” ran so erratically at Washington--even though it had won--that Fageol refused to drive it the following week at New Martinsville, West Virginia. (Joe Taggart drove Slo-mo-shun V in that race but failed to finish.)

For pure boat racing, it's hard to top the classic 1954 Gold Cup at Seattle. Indeed, boats ran head-to-head with each other all day long on that memorable August 7.

Slo-mo-shun V, driven by Fageol, finished first in all three 30-mile heats. But Lou had to win them the hard way--especially in Heat Two, when Slo-mo-shun V, Slo-mo-shun IV, and Miss U.S. shared the same roostertail for seven of the eight laps on a 3.75-mile course.

Slo-mo-shun V was also the first boat to achieve competitive results with a Rolls-Royce Merlin engine. (All of the Gold Cup winners from 1947 to 1953 used Allison power.) This particular Merlin was salvaged from the ill-fated Quicksilver of 1951.

A near-catastrophe marred the running of Heat Three. Lou was making one of his chillingly spectacular “flying starts” from under the Floating Bridge with Slo-mo-shun V when Wha Hoppen Too, driven by rookie Marv Henrich, emerged from the pits and cut straight across the path of the oncoming Slo-mo-shun V, which was running at top speed.

Fageol and the “V” bounced perilously but managed to stay upright and went on to win the race, while Henrich was disqualified as a result of the incident.

Following his victory in the 1954 Gold Cup, Fageol announced his retirement from competition. He mentioned the name of the future Unlimited Class superstar, Bill Muncey, to Stan Sayres as a possible replacement. Nothing came of the suggestion as Lou returned in 1955 for what would prove to be his final appearance as a driver.

From the outset, the 1955 Gold Cup seemed predestined to go down in history as one of the more memorable--and controversial. The first indication came in the form of a bombshell, dropped by referee Mel Crook. In a declaration aimed at Lou Fageol, Crook threatened disqualification for reasons of safety to any contestant attempting a "flying start" from under the Lake Washington Floating Bridge. The resulting storm of negative reaction prompted Crook--a former champion Unlimited driver in his own right--to resign his post in protest.

On Friday, August 5, 1955, the "flying start" issue was rendered moot when Fageol and Slo-mo-shun V turned a complete backward somersault at 165 miles per hour during a qualification trial. Lou was badly injured and the boat had to be withdrawn.

Danny Foster and Tempo VII were the first to qualify at a record-breaking 116.917 for three laps of 3.75 miles each. This new mark stood for exactly ten minutes until Joe Taggart wheeled Slo-mo-shun IV to a reading of 117.391 with a single lap of 119.575.

Fageol, as defending champion, wanted to be fastest qualifier. Lou equaled, on his first two laps, the record time of teammate Taggart with identical readings of 117.391. On the third backstretch, a new speed mark seemed imminent as the Slo-mo accelerated toward the final turn at a frightening pace.

KING-TV of Seattle then recorded what is perhaps the most famous few seconds of film footage in hydroplane history.

Slo-mo-shun V leaped clear of the water, turned a complete 360-degree backward somersault, landed upright, minus her driver, and coasted to a halt. Rescue teams found the stricken Fageol still conscious, despite four fractured vertebrae, four broken ribs, a punctured lung, and a permanently damaged heart. This was Unlimited racing’s first blow-over accident.

It is speculated that if Lou had been able to complete lap-three of his qualification attempt, he might have reached an unheard of 122 miles per hour.

The flip brought down the curtain on his racing career. After several years as a respected elder statesman of the sport that he loved, Fageol passed away on January 27, 1961.

According to his son Ray Fageol, Lou’s death was directly attributable to the injuries suffered on August 5, 1955.

History has not been kind to Lou Fageol. Many believe that he went too fast and took too many chances, while others believe him to be one of the all-time great drivers--with the guts and the talent necessary to win races.

Not long before his death, Lou acknowledged his respect for the awesome machine that is an Unlimited hydroplane: “It always scared hell out of me to drive one. And if it doesn’t scare hell out of you when you get behind a wheel, you’d better not drive, because you’ll kill yourself.”