Donald Campbell

Donald Campbell: The Man in the Shadow

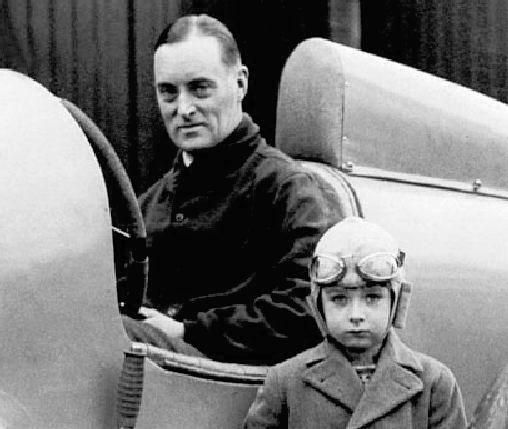

There's a grainy old newsreel which raises a hundred unanswered questions about the relationship between Donald Campbell and his illustrious father, the joint architects of 11 speed records on water and 10 on land, and all of them created for the glory of the Old Country. On the film a young and evidently nervous Donald rushes to greet Sir Malcolm at Southampton Docks. It's 1933, and the great hero has just boosted his own land speed record to 272 mph. In the poignant vignette the boy goes to shake the man's hand, but the man appears not to notice.

I once mentioned that footage to Donald's widow, Tonia Bern, who clapped her hands excitedly. "I know! I know the film you mean! You know, it was watching that film, when Donald showed it to me, that made me fall in love with him! There was this little boy, so proud of his father, and his father didn't even notice..."

Maybe Tonia was right. Maybe Sir Malcolm simply wasn't the demonstrative type. Maybe he just didn't notice his son's gesture. But few relationships between public figures have been as complex as that between the Campbells. Sir Malcolm was a hero. A self-made man who let nothing stand between him an d his ambitions, he was an upper middle class product of all that England stood for between the wars. Arguably, he was the greatest speedking of them all.

As a parent he was tough, and stories abound of his harsh treatment of a son who was frequently rambunctious. There was the tale of the expensive railway set Malcolm bought him. Pathe News has film footage which shows a homely scene where the train derails after Donald sets the points incorrectly, and father says to contrite son: "I'm afraid you've broken this, old chap." Some suggest things were rather less quaint beyond the camera, which Sir Malcolm controlled as a Pathe director. Certainly, he later took over the train set for himself, allowing Donald access to it only on request.

Then there was the story of the dinner party, at which Sir Malcolm was alleged to have choked a proper goodnight out of his son after Donald had stumbled over his farewells to guests as he prepared for bed. But Donald's younger sister Jean is adamant that they enjoyed a wonderful childhood, and denies such abuses ever occurred. "Father was strict, sure, but Donald was always wild, and after some of the things we got up to, it's hardly surprising that Father's nose would twitch!" They came from a privileged background, but they did the things ordinary, spirited, kids tend to do. They set light to haystacks, or pulled machinery apart only to discover their own shortcomings when it came to reassembly. Eventually eight year-old Donald was sent off to prep school, where he honed his business acumen by selling his father's autograph and unashamedly basked in the reflected glory of having the fastest man on earth as a parent.

Stern disciplinarian or not, Campbell senior had enough of the small boy in himself to have pursued the romantic notion of hunting buried treasure during an unsuccessful expedition to the Cocos Islands in 1926 with his friend Kenelm Lee Guinness. Few boys would not have looked up to such a swashbuckling figure. Freud might have had a field day analysing the relationship, but no matter what Malcolm might or might not have been as a father, Donald worshipped him. But while the Old Man was alive there was only room for one record breaker in the household. And Sir Malcolm once ventured the opinion that Donald was so accident prone that he would kill himself if he tried.

When Donald finally took over his mantle, everything he would do in record breaking had that edge, would always be done with the thought in mind: Would the Old Man have approved? Despite his feelings for his father, Donald Campbell was far from a colourless individual with no personality of his own. But he never truly emerged from his father's long shadow, which would influence his mannerisms and, most certainly, his refusal to give up. He lived his life on his own terms, but was forever trying to prove to himself that he could do the same great things, that he was worthy of his father's name.

He was so trapped within that shadow that, no matter what he achieved - and most historians reckon that he was far greater than his father on the water - he would never feel it was quite good enough. Part of him wanted to do better than his father, but the boy within him wanted to preserve that legend. Father and son had charisma in spades, allied to an awesome determination beyond the understanding of ordinary men, and a promiscuous streak that was much easier to figure out.

Donald inherited his father's flamboyant manner and the tendency to exaggerate, to embroider the tales he recounted. He also inherited the Old Man's refusal to start something he couldn't finish. In the early days with the 350 hp Sunbeam Malcolm had broken the land speed record three times, only to be denied official recognition on technicalities. That initial failure spurred him on. Had he won the record easily, he might have moved on to something else. Instead, the fight became an obsession that never left him. Malcolm Campbell lived in an age that feted its heroes and ignored their human weaknesses. He succeeded in almost everything he tackled. In record breaking, once he'd got the old Sunbeam up to official speeds, his only real failures were at Verneuk Pan in South Africa in 1929, and Coniston in 1947 with the jet version of the pre-war Bluebird K4.

Donald would be acutely aware of this, when he went to Bonneville with the Bluebird CN7 car in 1960; when he took the new version to Lake Eyre in 1963 and early 1964 when the rain washed him out; and when there was all the hanging about at Coniston in 1966. A combination of luck, ruthless determination, sufficient personal wealth and financial backing to do the job without compromise, not to mention the support of an adoring nation, helped Sir Malcolm to venture forth time and again to slay dragons and never really come close to getting singed by their breath. But for Donald it was all very different. He was born out of his time, and as the Fifties became the Sixties, younger, trendier icons stole the spotlight.

When he took over Sir Malcolm's Bluebird K4 in 1949, only months after the Old Man's death, it was with the same bloody-mindedness that would ultimately seal his fate. Recordbreaker Goldie Gardner had told him of American industrialist Henry Kaiser's plans to break the record with an Allison aircraft-powered boat called Aluminum First. And history repeated itself; initial problems only served to put the spurs to his challenge. On the first try they told him he had broken the record, only to discover an error. In 1951, after Stan Sayres and Ted Jones had wrested back the record for America with the remarkable Slo-Mo-Shun IV, K4 was disembowelled on Coniston when Donald and faithful engineer Leo Villa were lucky to survive a 170 mph collision with a submerged railway sleeper.

After all the heartache a lesser man would have thrown in the towel, but Campbell took Slo-Mo's second record and then John Cobb's death a year later as the spurs to carry on. Thus, from Donald Campbell's limited personal wealth and boundless determination, was born the jet-propelled Bluebird K7.

Leo Villa was the adhesive which held the Campbell attempts together. A feisty, intuitive mechanic, he had gone motor racing in the Twenties with the Italian Guilio Foresti after hurling ink over the hall porter had finally terminated his career as a page boy at Romano's hotel in London's Strand. He had been Sir Malcolm's paid employee, but he was much more than that to the easy-going Donald. He had known the boy almost since he had been born, and was friend, father confessor and trusted lieutenant rolled into one. Donald called him Unc.

Donald was intensely superstitious. No attempt after 1958 could start without Mr Whoppit, the Merriweather teddy bear given to him that year by manager Peter Barker. He so hated the colour green that 1964 project manager Evan Green was known within the team as Evan Turquoise. He refused to use the head-up display on the Bluebird CN7 car because it used a green light. Smiths technician Ken Reaks recalls: "He said to me, 'That's green, isn't it?' And I managed to persuade him it wasn't, but though he accepted that, he still didn't like it." He hated anyone wishing him 'Good Luck' after the boatman at Coniston, Goffy Thwaites, had said it prior to the 1951 accident with K4. He rubbed a little Polynesian doll mascot, and his fanatical interest in spiritualism more than once led him to try and contact his father.

The Fifties were his golden years, when he vied for national newspaper headlines with test pilot Neville Duke and his unrelated motorcycle racing namesake Geoff Duke, and Grand Prix aces Stirling Moss and Mike Hawthorn. He was the playboy adventurer who, like his father, had the knack of stamping his aura on any gathering that he joined. Like them all, he lived with death as a shadow at his shoulder. When K7 was being designed, he had watched film over and again of Cobb's accident on Loch Ness with Crusader. And the new boat was well advanced by October 1954, when the Italian champion, Mario Verga, perished on Lake Iseo in his Laura 3. He kept going.

Bluebird K7 was powered by a Metropolitan-Vickers Beryl jet engine of 4000 lb thrust. It was taken to Ullswater early in 1955, but suffered many teething troubles. It was not until designers Ken and Lew Norris had made many modifications that he was ready to attack what he liked to call the 200 mph 'water barrier'. On 23 July that year Campbell overcame all his problems to achieve 202.32 mph. Later that season Bluebird sank while on test at Lake Mead in Nevada, but the craft was raised and repaired and on 16 November he boosted his own record to 216.20 mph.

Like father, like son. In the Fifties holiday magnate Sir Billy Butlin offered £5000 annually to anyone who broke the record, and each year as he recouped his investment, Campbell would nudge it a little higher: 225.63 mph in 1956; 239.07 in 1957; 248.62 in 1958; and 260.35 in 1959. He was on top of the world.

Then came the interlude with the Bluebird car, a gas-turbine-powered monster which drove through its wheels and was thus already a White Elephant when he crashed it around 300 mph at Utah in 1960. There had been appalling pressure for a quick result, to put his four American rivals in their place, and to justify the astonishing expense. Instead he accelerated too hard, lost traction, and rolled the car. He sustained a fractured skull, but typically insisted on walking into the hospital at Tooele.

On July 17 1964 his moment of truth finally came. On a track on Australia' s Lake Eyre that was still wet from recent rain, and far shorter than he and Norris had wished, he averaged 403.1 mph. He had faced down his own demons that were a legacy of Bonneville, and a dreadful course which tore matchbox-sized chunks of rubber from his tyres as Bluebird cut four-inch ruts. And he won through by a hair's breadth after an abnormally brave performance. But it was a qualified success. Craig Breedlove had done 407 mph the previous year, and even if his pure-jet Spirit of America didn't confirm with the rules about driving through its wheels, the figure was all Joe Public cared about.

Three months later, after jet cars had been ratified, Campbell's hard-won record was annihilated. On the last day of December Campbell hit back as only he could, setting his seventh and final water record at 276 mph on Australia's Lake Dumbleyung. This was the first time anybody had set the world land and water records in the same year, a unique achievement that is never likely be challenged. It was his finest hour. Yet he was stung by what he perceived as lack of interest when he announced plans for a supersonic rocket Bluebird with which to regain his land speed crown, and after slotting a more powerful Bristol-Siddeley Orpheus engine into Bluebird K7 he sought to rekindle the flame of publicity by taking her to Coniston Water for a crack at the 300 mph barrier.

He arrived late in 1966 as the winter edged around his small camp. Problems chased one another through the boat, and after a catalogue of delays and dramas came that final, fatal run on January 4, 1967. He recorded 297 mph running north to south, but for an unaccountable reason headed straight back down the course without refuelling. As he met his wake from the first run, Bluebird began tramping until, at a speed estimated by some as 328 mph, but which Ken Norris believed was much lower as Donald had begun to back off, Bluebird climbed inexorably into the sky before flipping back into the murky waters of the lake. Like his father, Donald Campbell was intensely chauvinistic. "Donald was a very patriotic boy," a broken Leo Villa told those who had tried so hard to find Campbell's body. He was also a fatalist. Shortly before his death he had played cards, and had turned up the Ace and then the Queen of Spades. The same combination had signalled the end for Mary, Queen of Scots, Donald had looked quietly at the cards, and said: "Someone in my family is going to get the chop. I pray God it's not me, but if it is, I hope I'm going ruddy fast at the time." He was. I have often wondered since how those who had been so critical at Lake Eyre, those who had stood safely and questioned his courage and suitability from the touchlines, felt when they heard the commentary Donald Campbell was still making as he, Bluebird and one of the most inspiring legends of British history fell to their final resting place that grey morning on Coniston. Donald was every bit his father's son. He had all of Malcolm Campbell's guts; Fate just placed them in different ages, and obliged them to express themselves in different ways.

© David Tremayne. Used by permission.