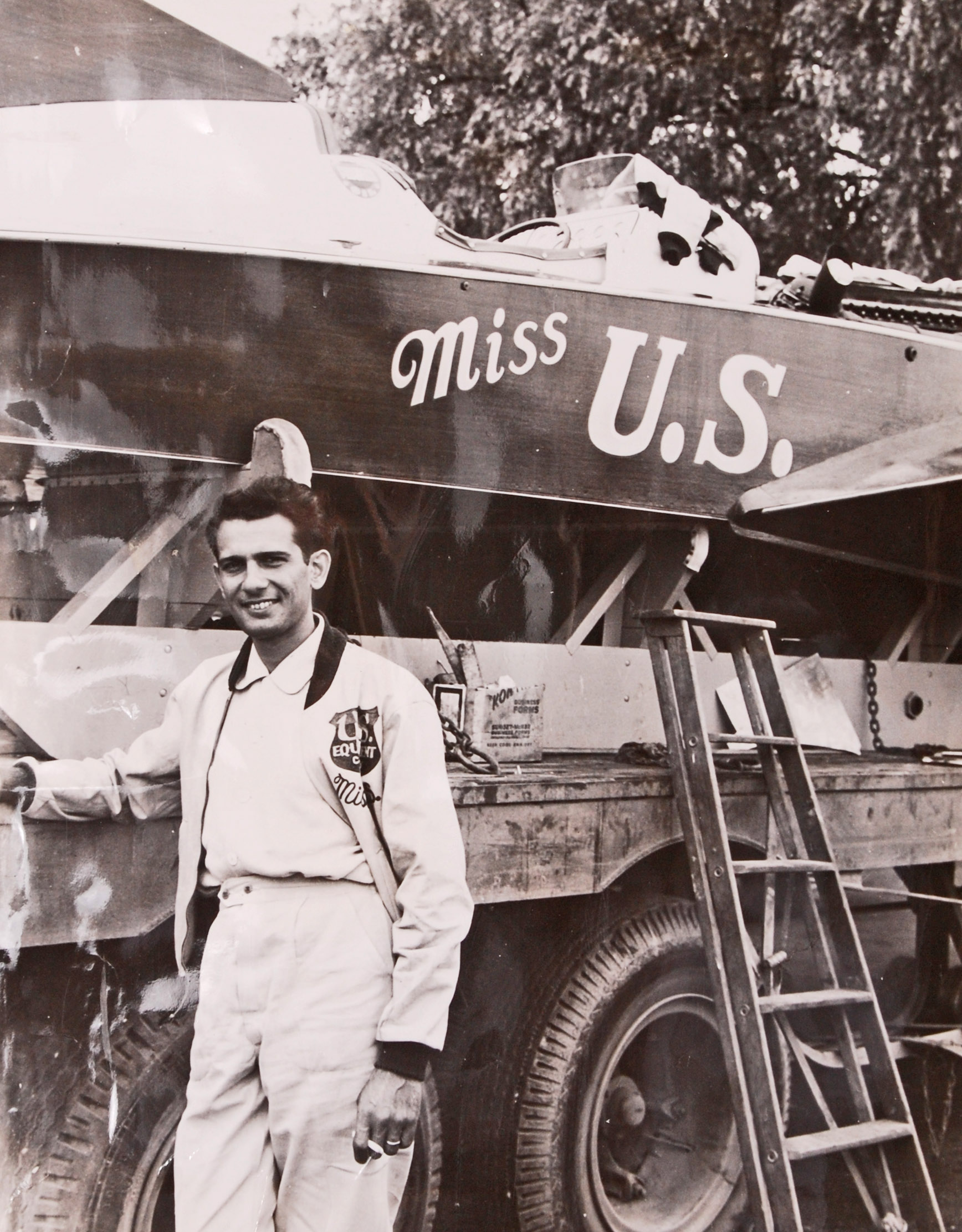

George Simon

George Simon Remembered

George Simon's Miss U.S. racing team initially appeared in 1953 and remained until 1976, except for a brief period of inactivity during 1971 and 1972.

The team won twelve major races with Jack Bartlow, Don Wilson, Fred Alter, Bill Muncey, and Tom D'Eath as drivers.

A U.S. Navy fighter pilot during World War II, George drove his own boat a few times in the early years. But as the father of ten children, he was encouraged to give up that activity.

Simon flipped the original Miss U.S. In the 1954 Maple Leaf Trophy at Windsor, Ontario, but rebounded a few weeks later to take second-place to Lou Fageol and Slo-mo-shun V in the APBA Gold Cup on Seattle's Lake Washington.

The first craft to carry the colors of the Detroit-based U.S. Equipment Co. into competition was a three-point prop-rider, designed by Dan Arena. In the 1955 Rogers Memorial at Washington, D.C., this Miss U.S. became the very first hydroplane to ever post an overall average race speed in excess of 100 miles per hour with Bartlow as driver.

Simon went all out to win the National High Point Championship in 1958. He sent his boat (the second Miss U.S. I) to twelve races but fell six points short of Ole Bardahl's "Green Dragon" Miss Bardahl at season's end. George nevertheless won four races that year: one with Alter in the cockpit (the International Cup) and three with Wilson at the wheel (the President's Cup, the Indiana Governor's Cup, and the Sahara Cup).

The George Simon team achieved one of its proudest distinctions in 1962 on Guntersville Lake in Alabama. With crew chief Roy Duby at the wheel, the Rolls-Royce Merlin-powered craft set a mile straightaway record for propeller-driven boats at 200.419 miles per hour. The record stood for 38 years.

The Miss U.S. boats won four races on home waters at Detroit. These were the 1956 Silver Cup with Wilson driving, the 1969 UIM World Championship with Muncey, the 1975 Gar Wood Trophy with D'Eath, and--the most memorable of all--the fabulous 1976 APBA Gold Cup. This was when pilot D'Eath held off a gutsy challenge from the Muncey-chauffeured Atlas Van Lines in the Final Heat to realize owner Simon's fondest dream after 23 years of trying.

George almost quit racing in 1974. This was after a disastrous fire gutted his new Ron Jones-designed cabover Miss U.S. at the ill-fated Sand Point Gold Cup in Seattle. But Simon ordered the Jones hull repaired because he still had not won a Gold Cup race.

Miss U.S. I had been fastest Gold Cup qualifier in 1959, 1960, and 1961.

At the 1961 Reno Gold Cup on Pyramid Lake, Wilson and Miss U.S. I finished first in Heats One and Three but had a DNF (Did Not Finish) in Heat Two. The heats consisted of ten laps around a 3-mile course.

Don was leading on the fifth lap of Heat Two when Russ Schleeh flipped the Miss Reno. According to Unlimited rules, the heat had to be stopped and re-run.

Miss U.S. I was only 200 yards from the finish line of lap-five when the heat was stopped. If Wilson had crossed the line, the half-way point of the ten-lap heat would have been reached and the heat would have been declared completed. This would have entitled Wilson to 400 points and certain overall victory.

In the re-run of Heat Two, Miss U.S. I conked out.

First-place in the 1961 Gold Cup ultimately went to Bill Muncey and Miss Century 21, which accumulated 900 points for three second-place heat finishes. This compared to 800 points for Don Wilson and Miss U.S. I.

But it all came together in 1976.

The Final Heat showdown between Miss U.S. and Atlas Van Lines climaxed one of the most competitive race days in Detroit River history. There was considerable equipment damage. Two top contenders--Miss Budweiser and Olympia Beer--were virtually destroyed

After three heats and 45 miles of racing, it all came down to Miss U.S., which had 1100 points, and Atlas Van Lines, which had 925.

Miss U.S. had been battling mechanical gremlins throughout the day. In Heat 2-B, the Allison engine had sputtered and lost oil pressure. And the stabilizer wing had come loose. But luckily for D'Eath, he had enough time to return to the pits for hurried repairs and come back out to win.

For the Final Heat, crew chief Ron Brown used an engine that the Miss U.S. team had not planned to use. They did not know if it had what it took to win. The power plant that they had intended to use was not working properly that day.

With both Budweiser and Olympia out of the race, the odds-on favorites had to be Bill Muncey and Atlas Van Lines. This was the former Pay ‘n Pak hull that Muncey had purchased from Dave Heerensperger the previous winter. It had won the two previous Gold Cups and the three previous National Championships.

Muncey also had the advantage of Rolls-Royce Merlin power, while D'Eath had to make do with a turbo-Allison.

Clearly, if George Simon's team--already scheduled for retirement at the end of the year--was going to win their one and only Gold Cup in 1976, they would have to earn it--the hard way. And that's exactly what they did.

Miss U.S. grabbed the inside lane at the start. At the end of lap-one, D'Eath led Muncey by three boat lengths.

Then Atlas Van Lines caught up with Miss U.S. In the Belle Isle Bridge turn of lap-two and powered into the lead, which it held for the next two laps. The partisan crowd collectively groaned. It appeared to be Muncey's race to win.

But it wasn't.

Miss U.S. overtook Atlas Van Lines with one and three-quarter laps to the checkered flag.

D'Eath averaged 108.021 for the Final Heat with Muncey checking in at 105.386.

The seven Gold Cup heats took more than eight hours to complete on account of the windy conditions and the accidents. The Detroit River could hardly have been more uncooperative.

But Simon got his Gold Cup.

One of the most important things that George ever did for the sport occurred not on a race course but in a Michigan court room. It's not generally known, but Unlimited hydroplane racing almost died in the early 1960s when the Internal Revenue Service started cracking down. The government claimed that the Unlimited owners were indulging in a hobby rather than a business endeavor.

Joe and Lee Schoenith lost their battle with the IRS. But George Simon managed to win his (in 1963). One of the unfavorable aspects of the Schoenith case had to do with Joe going for a joy ride in Gale III at the 1957 Detroit Memorial Regatta. This cost the Schoeniths a hefty figure in the six digits, which--in those days--was a huge amount of money.

George Walther, Jr., played an important role in Simon's tax case. The IRS, in that situation, upheld Simon's contention that Unlimited racing was a legitimate business expense (within specified guidelines) and thereby tax deductible. Simon introduced records which demonstrated that his U.S. Equipment Company's volume of business had increased substantially during the years that Simon had been involved in racing--and with no other change in normal business promotion.

Walther testified how he had met Simon at an Unlimited race in the 1950s. They became friends. And Walther eventually became Simon's customer.

The favorable IRS ruling helped to pave the way for major corporate involvement in Unlimited racing. On the strength of this ruling, Anheuser-Busch entered the sport in a big way in 1964 with the first in a long line of Miss Budweiser hydroplanes.

To keep the government happy, the sport had to "professionalize" itself. This included mandatory--rather than optional--cash prizes at all of the races. At this time, the Gold Cup rules were rewritten which required that the race location go to the city with the highest financial bid. This was a change from the time-honored tradition of awarding the Gold Cup to the yacht club of the winning boat.

The friendship between George Walther and George Simon, by the way, led to David "Salt" Walther, George's son, being hired as pilot for Simon's Miss U.S. team in 1970.