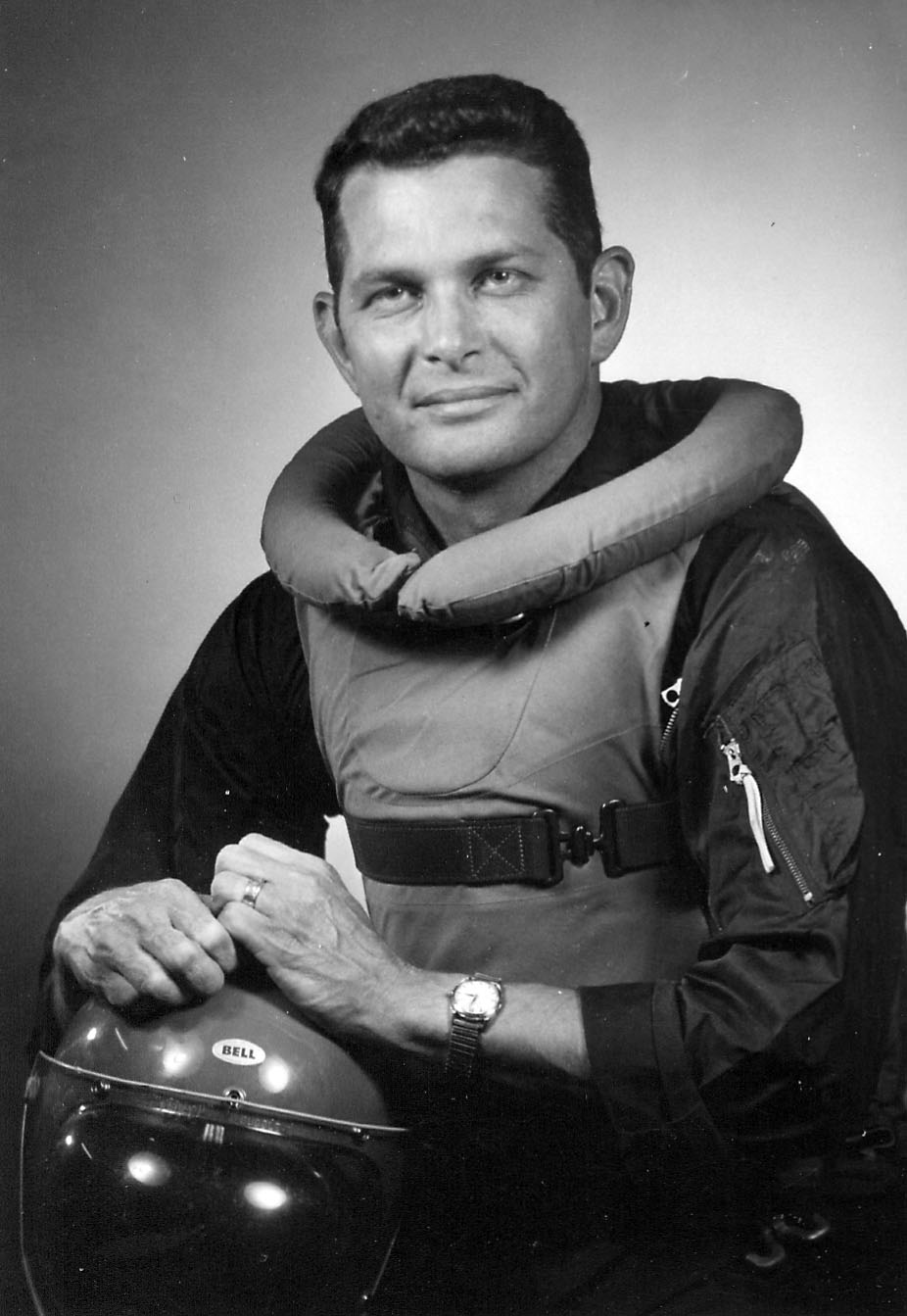

Jim McCormick

The Jim McCormick Story

The only driver to score back-to-back victories with Miss Madison, Jim McCormick first served notice of his competitive prowess when he won the 266 Cubic Inch Class race at the 1964 Madison Regatta with Miss Kathleen.

An air conditioning contractor from Owensboro, Kentucky, Jim's first competition in an Unlimited hydroplane was at the 1966 Tampa Suncoast Cup with Miss Madison (U-6) where he piloted the community-owned craft to a third-place finish with a victory in the first heat. During 1966, he completed all but two of the 19 heats in which he started with Miss M and finished eighth in a field of 23 drivers in the National High Point Standings.

After starting the 1967 season with Notre Dame, he replaced owner Bob Fendler in the cockpit of Wayfarers Club Lady and went onto place third in a field of 22 drivers in the National Standings. While driving the Wayfarer, he set the fastest qualifying marks at each of the Atomic Cup, Gold Cup, and British Columbia Cup races with speeds of 110.837, 118.507, and 112.782--the latter a world record for a 2-1/2-mile course.

In 1968, McCormick divided his time between Atlas Van Lines (U-35) and Harrah’s Club (U-3). His best finish was a third at the Arizona Governor's Cup with Harrah’s Club. While driving the U-3, he was the only driver to defeat National Champions Billy Schumacher and Miss Bardahl three times in heat competition--twice at Seattle and once at Phoenix.

In 1969, Jim returned to Miss Madison, which he drove in four Eastern races and placed third in the Madison Regatta. For the Western tour, he handled Atlas Van Lines (U-19)--the former Wayfarers Club Lady--and posted the highest finish of his career thus far--a second-place at the Seattle Seafair Regatta.

It is interesting to note that, twice in his career, McCormick was called upon to bail out a major team that had started the season with a highly touted rookie driver who ultimately couldn't make the competitive grade. In 1968, he replaced Burnett Bartley in Harrah’s Club and, in 1969, he succeeded Earl Wham in Atlas Van Lines.

Both Bartley and Wham came to the Unlimited ranks with impressive credentials from the Limiteds. But as Unlimited drivers, they were total non-entities. Enter Jim McCormick. All of a sudden, the boats were contenders with significant increases in heat speeds.

For the next two seasons, Jim drove exclusively for Miss Madison, although he almost missed the 1970 campaign entirely. Miss Madison was involved in a highway accident in Georgia while en route to the first race of the season in Tampa, Florida. Pulled off the circuit, the stricken craft underwent repairs by original builder Les Staudacher. In retrospect, the mishap was probably a blessing. Staudacher used the occasion to go through the entire hull and fix several things in addition to the highway accident damage that might otherwise have gone unnoticed.

The end result was an improved contender when Miss M returned to action a month later. Had the National Championship been determined that year solely on the results of the five races that the Miss Madison did enter, discounting the three that she missed, the team would have finished fourth instead of sixth.

Jim and Miss M defeated the highly regarded Tommy “Tucker” Fults and Pay ‘n Pak’s ‘Lil Buzzard in Heat 1-B at Madison, which was a surprise. The U-6 also showed a lot of class--and a definite increase in speed -- when she and McCormick trounced the favored Bill Muncey and Myr Sheet Metal in both Heats 1-C and 3-A of the season-concluding San Diego Gold Cup.

At year’s end, Miss Madison was running the best of her long career and giving the better-than-average performance that was expected of her. She could make the front runners work for it and could run with them on occasion. But the general consensus at the outset of 1971 was that only a newer hull and more power would put the U-6 team in the winner’s circle.

Nevertheless, the Miss Madison organization decided to stay with their eleven--going on twelve--year old craft for one more season.

The 1971 campaign started with a new race, the Champion Spark Plug Regatta, on Biscayne Bay at Miami Marine Stadium. Miss M was leading in both of her preliminary heats but was forced to drop back on account of a fuel mixture problem in section 1-A and a faulty supercharger in 2-B. Not to be denied a spot in the finale, the volunteer crew members proved their mettle by performing a complete engine change in less than thirty minutes. Pilot McCormick then proceeded to take second spot in both the Third Heat and the overall standings behind Dean Chenoweth and the Miss Budweiser.

Miss Madison continued in the Champion Regatta a resurgence that had begun in the last race of 1970. No longer was the U-6 thought of as a slightly better-than-average boat that was merely along for the ride. The Miss M was now regarded as a viable contender. However, the team was still short on money and horsepower, and most people still refused to take the community-owned boat seriously.

Moving on to the President’s Cup contest on the Potomac River, Miss Madison won her first two heats convincingly. She defeated the likes of Billy Schumacher in Pride of Pay ‘n Pak, Leif Borgersen in Hallmark Homes, and Billy Sterett, Jr., in Notre Dame, each of which had a millionaire owner and used the more powerful Rolls-Royce Merlin engine.

Prior to the finale, Miss M and Jim McCormick were not an illogical choice to win the race, based upon their strong showing in the preliminary action. Charging into the first turn of the Championship Heat, however, the U-6 was hosed down by the roostertails of Hallmark Homes and the eventual winner, Atlas Van Lines I, handled by Bill Muncey. McCormick managed to restart and take a disappointing fourth behind Hallmark, Atlas I and Miss Budweiser, although he managed to overtake and outrun Pride of Pay ‘n Pak by a wide margin.

The Miss Madison team won the overall second-place President’s Cup trophy for 1971 and had the satisfaction of running both the fastest 15-mile heat and the swiftest 45-mile race of the contest. But driver McCormick was bitterly discouraged. He had missed victory by a scant 31 points and was beginning to wonder if winning a race wasn’t perhaps an impossible dream.

In the Kentucky Governor’s Cup at Owensboro, Miss M did not improve on her two previous performances, taking an overall third behind Atlas Van Lines I and Pride of Pay ‘n Pak. The U-6 challenged Miss Budweiser for the lead in Heat Two, but otherwise her performance was undistinguished.

At the Horace E. Dodge Cup in Detroit, Miss Madison ran head-to-head with Terry Sterett and Atlas Van Lines II (the former Myr Sheet Metal) in the First Heat, despite rough water. On the last lap, Sterett moved ahead of McCormick and maintained this advantage to win by three boat lengths.

In the Second Heat, Miss M broke down and recorded her first DNF (Did Not Finish) of the year. Consequently, the U-6 was ineligible for the finale. Still, Miss Madison was running the best of her almost ended career.

The Thunderboat trail now led to Madison, Indiana, which was steeped in a competitive tradition that dated back to 1911. As things developed, the city’s 60th boat racing anniversary story would have amazed a fiction writer. No publisher would have accepted a make-believe script on the race.

For the first time since 1951, the Indiana Governor’s Cup shared the spotlight with the APBA Gold Cup, power boating’s Crown Jewel, which had never before been run in so small a town as Madison. Due to a technicality and a misunderstanding, the $30,000 bid for the race by the sponsoring Madison Regatta, Inc., was the only one submitted in time to the Gold Cup Contest Board.

For ten years, the volunteer Miss Madison mechanical crew had tried to win the hometown race without success. They faced an uphill fight in 1971, and they knew it. In the first four races of the season, Miss Budweiser and Atlas Van Lines I had both scored two solid victories apiece. Atlas Van Lines II, a five-race winner in 1969-70, was likewise a formidable contender. (Having been her team’s number one entry during the three previous years, the II’s performance had suffered little in her secondary role with Terry Sterett in the cockpit.)

Also, not to be overlooked in the pre-race figuring at the Madison Gold Cup were the Hallmark Homes, the Notre Dame, and the Pride of Pay ‘n Pak.

Hallmark was having a difficult season but nevertheless had championship credentials, being the former 1967-68 Gold Cup and National High Point-winning Miss Bardahl.

Notre Dame, a virtual copy of the Hallmark Homes, had a reputation as being a fast competitive boat, although she had never won a race.

Pay ‘n Pak was likewise having an uneven 1971 campaign. The Pak sported a radical new design. She was wider, flatter, less box-shaped, had a pickle-forked bow configuration, and had performed admirably on occasion. The craft had experienced a disastrous 1970 season, but there were a few who staunchly believed that if Pride of Pay ‘n Pak ever had the “bugs” ironed out of her, she would revolutionize the sport, and render obsolete all of the top contenders of the previous twenty years.

Several days before the race, Jim McCormick placed a crucial telephone call to Reno, Nevada. He requested and obtained the services of two of the finest Allison engine specialists in the sport--Harry Volpi and Everett Adams of the defunct Harrah’s Club racing team--who flew to Madison and worked in the pits alongside U-6 regulars Tony Steinhardt, Bob Humphrey, Dave Stewart, Keith Hand, and Russ Willey. Volpi and Adams are credited with perfecting the Miss Madison’s water-alcohol injection system.

Race day, July 4, 1971, dawned bright and warm with ten qualified boats prepared to do competitive battle. A crowd of 110,000 fans literally choked the small Mid-Western town of 13,000. The river conditions were good, but Miss M was down to her last engine, having blown the other in trials. This put the U-6 people at a distinct disadvantage, because, at that time, the Gold Cup Race consisted of four 15-mile heats instead of the usual three.

The race was less than thirty seconds old when Hallmark Homes disintegrated in a geyser of spray and sank in the first turn of Heat 1-A, after encountering the roostertail of Atlas Van Lines I. Hallmark pilot Leif Borgersen escaped injury, but his boat was totaled.

Miss Madison was drawn into Heat 1-B along with Towne Club, Miss Timex, The Smoother Mover, and Atlas Van Lines II. During the warm-up period, Smoother Mover joined Hallmark Homes at the bottom of the river when her supercharger blew and punched a hole in the Mover’s underside.

Miss M had the lead at the end of lap one but was then passed by Atlas II. On lap three, the Fred Alter-chauffeured Towne Club began to challenge Miss Madison for second place. McCormick and Alter see-sawed back and forth for several laps and brought the crowd to its feet. Miss M managed to outrun the Towne Club and hang on for second-place points behind the front-running Atlas II.

For the second round of preliminaries, Miss Madison matched skills with Miss Budweiser, Notre Dame, and Atlas I in Heat 2-B. Bill Muncey reached the first turn first with Atlas I, followed by Miss M. Budweiser and Notre Dame were both watered down by Muncey's roostertail, causing both to go dead in the water. Atlas I widened its lead over the field down the first backstretch and in the ensuing laps, while Miss Madison settled into a safe second. Miss Budweiser immediately restarted to follow Miss M around the course in third-place. Notre Dame also managed to restart but only after being lapped by the field.

At the end of 15 miles, Muncey and Atlas I received the green flag instead of the checkered flag, indicating a one lap penalty for a foul against Miss Budweiser and Notre Dame in the first turn for violation of the overlap rule. This moved Miss Madison from second to first position in the corrected order of finish. Miss Budweiser was given second-place, and Atlas I wound up officially in third after running seven laps before Notre Dame could finish six.

After another random draw, Miss M found herself in Heat 3-B along with Atlas II, Notre Dame, and Pride of Pay ‘n Pak.

As Bill Muncey was preparing to drive Atlas I before Heat 3-A, he received word that Referee Bill Newton had put him on probation for the next three races of the season. The probation had resulted not only from the foul against the field in Heat 2-B but also from the cumulative effect of similar infractions by Muncey in 1970 at Seattle and San Diego. The consequence of the probation was that any further violations by Muncey would result in an indefinite suspension from racing.

Unperturbed, Muncey made a good start in Heat 3-A and was chasing Dean Chenoweth and Miss Budweiser down the first backstretch when Atlas I sheared off her right sponson and started taking on water. Bill frantically tried to steer his wounded craft toward the bank on the Kentucky side of the river but was unable to do so. Atlas Van Lines I rolled over on its side about 100 feet from shore and slipped beneath the surface, forcing Muncey to abandon ship. Now, three boats rested at the bottom of the Ohio.

Terry Sterett and Atlas II entered the first turn of Heat 3-B in the lead and stayed there, but Miss Madison kept nipping at their heels. Pride of Pay ‘n Pak, running in third, tried to overtake Miss M, but the U-6 pulled away to maintain second position. On the last lap, Miss Madison came on hard to finish only two seconds behind Atlas II and four seconds ahead of Pay ‘n Pak.

After three grueling sets of elimination heats, the five qualifiers for the final go-around comprised Atlas II with 1100 accumulated points, Miss Madison with 1000 points, Pride of Pay ‘n Pak with 869, Towne Club with 750, and Miss Budweiser with 700.

As the sun started to set on that historic July 4, the race for the Gold Cup and the Governor’s Cup boiled down to Atlas Van Lines II and Miss Madison. Miss M had to make up a deficit of 100 points in order to win the championship. To do this, the U-6 would have to finish first in the final 15-mile moment of truth. This appeared rather unlikely since the combination of Terry Sterett and Atlas II had bested the team of Jim McCormick and Miss Madison in each of their four previous match-ups that season, twice on the Ohio River and twice the previous weekend on the Detroit River.

As the field took to the water for the last time, some of the hometown fans hung on to the hope that perhaps Atlas II would fail to start and thereby allow the local favorite to win the big race by default. But that was not to be. As McCormick wheeled Miss M out onto the 2½-mile course, there was Sterett, starting up and pulling out of the pit area right behind him. Thus, as the final minutes and seconds ticked away, the die was cast. If McCormick hoped to achieve his first career victory on this day, he would have to earn it--the hard way.

Meanwhile, the ABC “Wide World of Sports” television crew members, who were there taping the race for a delayed national broadcast, decided among themselves that Terry Sterett was a shoo-in for the title. Accordingly, they set up their camera equipment in the Atlas II’s pit area in anticipation of interviewing the victorious Sterett when he returned to the dock.

All five finalists were on the course and running. Moments before the one-minute gun, Miss Madison was observed cruising down the front straightaway in front of the pit area. Then, abruptly, McCormick altered course, making a hard left turn into the infield. He sped across course, making a bee-line for the entrance buoy of the upper corner. His strategy was obvious. McCormick wanted the inside lane to force the other boats to run a wider--and longer--course.

As the field charged underneath the Milton/Madison Bridge, four of the five boats were closely bunched with Fred Alter’s Towne Club on the extreme outside, skirting the shoreline. Miss Madison had lane one; Atlas Van Lines II had lane two and was slightly in the lead when the starting gun fired.

Sprinting toward the first turn, Pride of Pay ‘n Pak spun out. Atlas II made it into and out of the turn in front with Miss Madison close behind on the inside. As the field entered the first backstretch, the order was Atlas, Madison, Budweiser, Pay ‘n Pak, and Towne Club.

Then McCormick made his move. After having run a steady conservative race all day long, “Gentleman Jim” slammed the accelerator to the floor. The boat took off like a shot and thundered past Terry Sterett as if his rival had been tied to the dock.

The partisan crowd screamed in unison, “GO! GO! GO!” Even hardened veterans of racing were dumbfounded. An aging, under-powered, under-financed museum piece was leading the race and leaving the rest of the field to wallow in its wake.

McCormick whipped Miss M around the upper turn expertly and sped under the bridge and back down the river to the start/finish line. It was one down and five laps to go. The Atlas, the Budweiser, and the Pay ‘n Pak were closely bunched at this point as they followed Miss Madison around the buoys.

The crowd was going absolutely wild. In lap two, McCormick increased his lead. And, in lap three, he extended his advantage even more. It dawned on the “Wide World of Sports” crew that an upset was in the making. Frantically, the ABC-TV technicians scrambled out of the Atlas pit area and hustled their camera gear over to the Miss Madison’s pits.

Out on the race course, Sterett had shaken free of Budweiser and Pay ‘n Pak and was going all out after Miss M. He was fast on the straightaways, but not as fast as McCormick. The Atlas cornered well, but not as well as the U-6.

Miss Madison was running flawlessly, her 26-year old Allison engine not missing a beat. Jim McCormick was driving the race of his life. Together, the boat and driver made an inspired combination. Bonnie McCormick, Jim’s wife, who had averted her eyes during the first few laps, was now concentrating fully on the action, cheering her husband on at the top of her lungs.

Miss M received the green flag, indicating one more lap to the checkered flag and victory. By now, the community-owned craft had a decisive lead. Sterett was beaten, and he knew it. The Atlas pilot could only hope against hope that a mechanical problem or a driving error would slow the Miss M down.

But that didn’t happen. McCormick made one last perfect turn. The Miss M’s roostertail kicked skyward. The boat streaked under the bridge, past Bennett’s dock, and over the finish line, adding a new chapter to American sports legend, as pandemonium broke loose on the shore.

Firebells rang, automobile horns sounded, and the spectators went out of their minds with delight. Everybody, it seemed, was a U-6 fan and, whether they lived there or not, a Madisonian. Even members of rival teams were applauding the outcome of this modern day Horatio Alger story.

Miss Madison had beaten Atlas Van Lines II by 16.3 seconds in the Final Heat and was 4.2 seconds swifter for the overall 60 miles. McCormick and Sterett had tied with 1400 points apiece in the four heats of racing. According to [then] Unlimited Class rules, a point tie is broken by the order of finish in the last heat of the day. So, the U-6 won all the marbles. These included an engraved plate, that would say Miss Madison, to be added to the rows of gleaming testimonials to the conquests of Gar Wood, George Reis, Danny Foster, Stan Sayres, Bill Muncey, and others.

It was the biggest day in the history of Madison, Indiana. It was Unlimited hydroplane racing at its best. It was a victory for the amateur, for the common man, a triumph that everyone could claim as his own. And not since the Slo-mo-shun days in Seattle during the 1950s had such an outpouring of civic emotion occurred at a Gold Cup Race with people celebrating in the streets until 10 o’clock that night.

Deliriously happy Miss Madison crew members carried pilot McCormick on their shoulders to the Judges’ Stand. Veteran boat racer George N. Davis, a mentor of McCormick’s during Jim’s 280 Class career, wept unashamedly at this, his protege’s, moment of triumph.

After receiving the Gold Cup from 1946 winner Guy Lombardo and the Governor’s Cup from Indiana Governor Edgar Whitcomb, a tired but happy McCormick explained his race strategy to the assembled legion of awe-struck media representatives. “We planned to take it easy in the early heats, and then let it all hang out in the finals.”

McCormick was the first to give credit where credit was due. He quickly acknowledged that without the mechanical prowess of his volunteer pit crew, victory would have been impossible. “These guys have been working their hearts out getting ready for this. They deserve all the credit.”

The Miss Madison crew received the Markt A. Lytle Sportsmanship Trophy at the Gold Cup Awards Banquet, where tribute was also paid to the two former Harrah’s Club team members - Volpi and Adams - for their invaluable help in winning “the big one”.

“Gentleman Jim” McCormick, who had achieved his “Impossible Dream," was the hero of the day, and he gratefully acknowledged the enthusiasm of the crowd. For several hours after the trophy presentation, McCormick, still in his driving suit, remained at the Judges’ Stand, signing his name for one and all. “Let the people come,” he said. “I’ll sign autographs as long as I can write.” It was the perfect ending to a perfect day.

As the spectators and participants drifted back to their own lives, one thought was uppermost in the minds of many: “Was it all a dream, or did today really happen?”

Yes, it did happen. And it happened again three weeks later on the Columbia River at the Tri-Cities, Washington. That’s when Miss Madison driver McCormick, and crew members Steinhardt, Stewart, Humphrey, Hand, and Willey made the incredible seem commonplace. They won the sixth annual Atomic Cup Race and, in so doing, moved from second to first place in the National Season Points chase.

Entering the Final Heat in fourth place in regatta points with two second-place finishes, Miss M was again lightly regarded as a title threat. The boat’s nitrous oxide system (which gives the craft an added burst of speed coming off the corners) had failed to function during the first two heats. In fact, the crew wasn’t even certain if the engine was going to start for the finale. But, in McCormick’s words, “We got it all together,” and not a moment too soon.

Most attention centered on Billy Schumacher in the Pride of Pay ‘n Pak and Bill Muncey in the now repaired Atlas Van Lines I, who led the field with only 100 points separating them. The futuristic Pay ‘n Pak looked especially formidable that day and seemed on the verge of coming into her own. Although, many experts were still siding with Atlas I to win due to that boat’s superior record on the Eastern tour.

Again, Miss Madison moved to the inside lane before the start and stayed there. The first corner was tight with four of the five finalists closely bunched. Miss M exited the first turn in the lead with Notre Dame, Pride of Pay ‘n Pak, and Atlas Van Lines following in close pursuit and Miss Timex trailing. So evenly matched were the first four boats that they appeared as one long continuous roostertail down the first backstretch.

Miss Madison finished the initial lap one fifth of a second ahead of Pay ‘n Pak and two fifths of a second ahead of Notre Dame with Billy Sterett, Jr. As the boats went through the first turn of lap two, Miss M started to pull away, while Pay ‘n Pak dueled with Notre Dame. The Pak moved away from Sterett on the second backstretch as Notre Dame lost power and slowed way down. Schumacher tried to challenge front-running McCormick but, in so doing, blew his engine and went dead in the water.

Meanwhile, Atlas Van Lines had gone past the ailing Notre Dame and then moved into second-place. By this time, Miss Madison had an enormous lead and was putting added distance between herself and the Atlas. Jim McCormick was flat out-driving his more powerful and heavily financed rival. Now no longer considered an upset threat to win, the U-6 was making it all look easy.

At the checkered flag, Miss Madison had a full 22-second lead over Atlas Van Lines. Then came Notre Dame, followed by Miss Timex, which was lapped by Miss M on the leader’s last time around the course.

In winning the Atomic Cup, Miss Madison became the first Tri-Cities champion to do the honors with an Allison engine as opposed to a Rolls-Royce Merlin. Miss M also became the first Allison powered craft since 1966 to score consecutive race victories in the Unlimited Class.

“This is really sweet,” beamed a jubilant McCormick. “This should prove to some race fans that our Gold Cup win wasn’t a fluke.”

The Miss Madison team’s triumph was now complete. “We’re number one!”, they proudly proclaimed. At long last, they stood at the very top of the racing world. In a sport dominated by millionaire owners and large corporate sponsorships, no one could afford to take the low budget U-6 for granted on the race course.

Following her back-to-back victories on the Ohio and Columbia Rivers, McCormick and Miss M competed in three more races. They blew an engine and didn’t finish at Seattle but quickly regained their commendable form at Dexter, Oregon, where Miss Madison took a strong second place to Pride of Pay ‘n Pak, the experimental craft that had finally gotten its act together. The Pay ‘n Pak was not significantly faster on the straightaway than the other top Unlimited hydroplanes of post-1950 vintage. But, with her low profile/wide afterplane design, the Pak could corner more efficiently than any previous boat in history. Handled by Billy Schumacher, Pride of Pay ‘n Pak became the first to reach a speed of 121 mph on a 3-mile course at the 1971 Seattle Seafair Regatta.

The boat of the future had arrived as the first in a new and faster generation of Thunderboats. The handwriting was on the wall. Inside of two years, every boat would have to be a Pay ‘n Pak design to be competitive.

In the twinkling of an eye, Miss Madison was obsolete. The days of the box-shaped hull with the narrow transom and the shovel-nosed bow were gone forever. The craft that had debuted so many years earlier as Nitrogen Too had seen its better days. It was time to make way for the new generation of world class race boats.

On the last day of her career, September 26, 1971, Miss M took an overall third in the Atlas Van Lines Trophy Race at Lake Dallas, Texas, with a victory in Heat 2-A over Season High Point winner Miss Budweiser. The U-6 also tied down enough points to secure second place in the 1971 National Standings and thereby duplicate her 1964 accomplishment for overall performance during the season.

Miss Madison’s year-end box score read 26 heats started, 24 finished, six in first-place, thirteen in second, four in third, and one in fourth. This brought her all-time career total to an unprecedented 163 heats started, an even 150 finished, 26 in first-place, 53 in second, 46 in third, 21 in fourth, three in fifth, and one in sixth.

During the finale at Lake Dallas, the Miss M’s deck started to work itself loose. McCormick kept her going at a safe conservative pace, finished the heat, and brought the aging U-6 back to the dock for the last time.

A new Miss Madison represented the Ohio River town on the Unlimited tour, starting in 1972. Another Miss M carried on the tradition, beginning in 1978, followed by another in 1988. And while each of these boats represented their 13,000 owners well, it is still the Gold Cup-winning hull that inspires awe.

In mid-season 1971, Jim started an Unlimited team of his own. He purchased the former Parco's O-Ring Miss (U-8) and ran it as Miss Timex--although he finished the season as driver of the Miss Madison, while Ron Larsen handled the U-8.

In 1972, he campaigned two boats--the Miss Timex (U-44) and the Miss Timex II (U-8)--and drove the U-44 himself. In 1973, he owned and drove two boats--the Red Man (U-8) and the Red Man II (U-81).

While attempting to qualify the U-81 at Miami in 1974, the boat hooked in a turn and McCormick was thrown out. Jim suffered a serious leg injury, which left him with a lifelong limp. His relief driver, George "Skipp" Walther, was killed a few days later when the U-81 lost a rudder during a qualification run at Miami Marine Stadium.

McCormick returned to the driver's seat of the U-81 for the last two races of the 1974 season, taking a fifth at Madison and a fourth at Jacksonville, Florida.

In 1975, Jim briefly piloted Dave Heerensperger's Pay ‘n Pak (U-1) but retired from racing after a third-place finish in the President's Cup. McCormick honored a previous commitment to campaign the U-81 (as Owensboro’s Own) at his hometown Owensboro Regatta in 1975 but relinquished the cockpit to Howie Benns for that race.

Jim took one last sentimental journey as an Unlimited driver when he piloted the U-81, renamed Santa Rita Homes, at the 1977 Owensboro Regatta, where he finished eighth.

Between 1966 and 1977, Jim McCormick participated in a total of seventy Unlimited races and finished in the top three at nineteen of them.

Following his retirement from competition, McCormick suffered health problems and was for a time (in 1981) legally blind.

Following laser surgery, which partially restored his eyesight, McCormick returned to the sport one more time in 1988 as co-owner with Bob Fendler of Pocket Savers Plus, driven by Steve David.

Years later, Jim was approached by a motion picture production company that wanted to do a theatrical film on McCormick's life and his victory in the 1971 Gold Cup. The movie, which was titled Madison, went before the cameras in 1999 with screen actor Jim Caviezel in the role of Jim McCormick.

It was Jim’s dream that this movie be made. Prior to his death in 1995, he had planned to portray his own father in an earlier version of the script.

When the credits roll at the end of Madison, a montage of outtakes from the ABC Wide World of Sports telecast can be seen. Through the magic of motion pictures, Jim McCormick was able to appear in “his” movie after all.