Rex Manchester

Hard Luck Rex [1991]

by J. Mike Fitzsimmons

Mark Douty photo

The spray settled, and the thunder subsided. The waters of the Potomac were quiet again. The river had become a death-ridden battlefield. One of the casualties was Arlo Rexford Manchester. The 40-year-old driver had paid the ultimate price for victory. It was his first, last, and only win in a major unlimited-hydroplane regatta. The 1966 President's Cup ended the life of Rex Manchester. It ended, also, a winless career that belied the talent and tenacity this skillful driver displayed.

Rex Manchester was born on July 17, 1927, in Pullman, Washington. Separated from his natural mother and a brother, Manchester was raised by his father. He was taught from an early age to be an independent person: quiet, intelligent, and self-reliant. At the age of 16, Manchester enlisted in the United States Marines. Although below the required age for enlistment, Rex managed to bluff his way past the recruiters; and in late 1943, he found himself in the Pacific theater.

Manchester's detachment participated in the grinding fight for Iwo Jima; and it was in the heat of battle, while his unit was pinned down by Japanese fire, that Rex Manchester showed the bravery that would become a part of his future as a thunderboat chauffeur. Fellow Marine Henry S. Aber lay wounded, exposed to constant enemy fire. Manchester risked his own life as he pulled his injured buddy out of harm's way. For his bravery, Rex Manchester was awarded the Bronze Star.

Henry Aber recovered, and at war's end returned to his home in Cleveland, Ohio, never to hear from Rex Manchester again. Repeated efforts to locate the man who saved his life met with failure. It was in 1966 that Aber learned what had become of his friend. News accounts of the tragic deaths at the President's Cup brought the name of Rex Manchester to the attention of his wartime companion once more.

At the end of World War II, Manchester was discharged from the Marine Corps, and he sought employment in Alaska where returning servicemen believed opportunity awaited them. While residing in Alaska, Rex Manchester and his friends participated in amateur powerboat racing events. Manchester became adept at handling D-utility, B-utility, and B-outboard hydroplanes, frequently capturing the prize at locally organized racing events. By 1956, Rex Manchester had distinguished himself by winning the Alaska National Championship and the grueling Alaska 300 Marathon. The Marathon was something of an infamous, offshore event that often ended with authorities searching for lost participants among the islands and inlets as the racers became disoriented and ran out of fuel or daylight while looking for the finish line. Manchester himself was the object of a search in at least one Marathon event.

By 1958, Rex Manchester had returned to his native Inland Empire; and while working in Spokane, he took up boat racing again, this time the inboard variety. In Seattle that summer, driving the hot 280 Miss Peppermint, Manchester placed third in the Inboard Nationals on Lake Washington. The Miss Peppermint was owned and driven by Manchester, but his attention was attracted to a quick 266 cu. in. hydro campaigned by the Miss Spokane Hydroplane Association, the Lil Miss Spokane. Actually, Manchester looked beyond this smaller charger to the unlimited Miss Spokane; though at that time Dallas Sartz and Norm Evans were posting respectable performances in the big sister hydro; and Rex was not considered as a replacement.

Steady performances in the Lil Miss Spokane won Manchester desired attention from the powers behind the Miss Spokane, and in early 1959, Manchester was invited to handle the unlimited in a Newman Lake test run. Immediately, Rex Manchester wanted the permanent driving assignment. Somehow he charmed the sponsoring committee into additional test runs, and by late spring, Manchester had become fully adapted to the larger, heavier, more powerful hull and impressed the owners into signing him for the '59 tour. Beyond driving, Manchester had devoted himself to serving the crew as a working member whose extra set of hands on a low-budget, all-volunteer team was gratefully accepted.

The year 1959 was a learning experience for Rex. The underfunded Miss Spokane was limited in mechanical prowess. Driving was critical to her success. Manchester performed well despite obstacles but was unable to drive to victory.

In 1960, things improved. The boat was a seasoned competitor, and Rex Manchester had honed his driving skills to a level where the competition respected him as a threat. Early in the season, Rex and the "Lilac Lady'' found themselves leading the field into the final heat of the Apple Cup. The Miss Spokane was the day's hottest contender on Lake Chelan, but Manchester's day ended under tow as his fragile Rolls-Merlin expired coming out of the first turn of lap one of the final, leaving him a spectator. He blamed himself. The crew felt he had been too hard on the equipment. There was tension, but there was no question that Rex Manchester was a promising unlimited driver.

In Seattle, the Miss Spokane crew hoped for a win. The boat was well prepared though still not well funded. Rex Manchester's seventh-place finish troubled him. Mechanically, the boat was not competitive. Manchester blamed himself. The crew did not agree. He drove well, but the boat was not running like a winner and could not finish the race.

The 1960 Gold Cup was run on windswept Pyramid Lake, Nevada. Although the dollars were tight, the Miss Spokane showed up with healthy equipment, and Rex Manchester qualified well. On race day, the water was beyond rough. Conditions were ugly. In his first heat appearance, Rex Manchester outperformed the competition, scoring a win. The second stanza found Miss Spokane running away from the field again.

On the beach, the crew was elated. Manchester, too, was euphoric about his performance. He mused in the cockpit as he rounded the buoys of the last turn just how he might acknowledge the checkered flag. He was excited and pleased with himself. Defending champion Maverick and prerace favorite Miss Thriftway had not done well in the preliminaries. Manchester knew that a safe third place in the final would win for him racing's most coveted prize. He was daydreaming and was for a fateful moment unable to see a vicious "hole" that awaited him at the exit pin.

The Miss Spokane buried the right nontrip, pitched violently, and in a second was upside-down. Rex Manchester was not thrown clear. Trapped in the inverted cockpit and held fast by the buoyancy of his life jacket, Manchester could not free himself. Panic overtook him. He felt the pain of leg injuries he had suffered, but his struggle was centered on getting to the water's surface. Rescuers reached the Miss Spokane quickly, and divers dislodged the helpless driver and brought him to the surface seconds before certain death. For Rex Manchester, the season was over. The Gold Cup eluded him and everyone else that day. Deteriorating weather brought an official declaration of "No Contest" in 1960, The race was not rescheduled.

Rex Manchester spent nearly three weeks in a Nevada hospital and thereafter several months recovering from his injuries. The Miss Spokane had survived the mishap and was scheduled for repairs, but the two would part company for awhile. Manchester was on the beach for most of the 1961 tour and returned to driving as pilot of Bill Schuyler's new $ Bill in 1962. The largely stock Allison craft was a solid Staudacher hull with a lot more power than Manchester was permitted to use. Schuyler insisted that Rex not exceed certain specified levels of speed and engine performance. Manchester felt that the cap on his efforts thwarted any chance of being competitive, although he recognized that the boat was capable of winning.

Money problems ended the community-supported Miss Spokane racing campaign; and in 1963, the hull was acquired in a confusing deal involving Seattle's Bob Gilliam, Miss Spokane crew member Kent Simonson, and eventually Dave Heerensperger, who returned the boat to competition as Miss Eagle Electric. Manchester found himself back at the controls of the familiar hydroplane, but '63 showed nothing worth writing home about. The boat did not handle like he remembered, although it was often faster than it had been previously. The year was spent in an attempt to dial in the craft after Rex experienced wild riding characteristics for most of the team's racing appearances.

In 1964, Rex Manchester and the U-65 parted a final time. For the most part, the able pilot was without a driving assignment. Manchester accepted a brief stint in the cockpit of Gale V in the Detroit Silver Cup event, but by the time the tour traveled west to Coeur d'Alene Lake for the Diamond Cup, he was again without a ride.

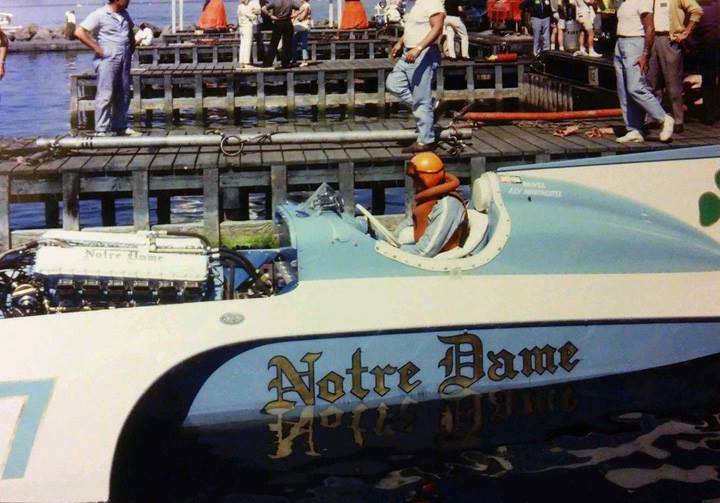

While Rex visited with friends in the Coeur d'Alene pits not intending to compete, he was summoned by the Notre Dame team. Bill Muncey, who had posted an impressive win in the new Notre Dame at Guntersville to open the season, was at odds with Shirley McDonald. Officially, he was not feeling well enough to drive. In fact, the relationship between Muncey and McDonald had been a volatile one, and Muncey was contemplating resignation.

Rex Manchester accepted a temporary offer to serve as relief driver for the "ailing" Muncey for just this one race. Clad in Muncey's too-small driving suit and feeling a little ridiculous, Manchester took his first ride in the powerful Notre Dame and was at once attracted to this well-groomed boat prepared by the skillful Jack Ramsey of Miss Thriftway fame.

Returning to the Coeur d'Alene pits wearing Muncey's uniform and helmet, Manchester had posted an impressive qualifying speed and had demonstrated that he could handle the Notre Dame with suitable skill. Moreover, owner Shirley McDonald liked this quiet driver who did not share Bill Muncey's propensity to hog the limelight.

Still, Manchester looked upon the driving offer as only a one-race opportunity, expecting Muncey to return to the cockpit at the next stop on the circuit, which he did. The crew was kind to Rex, but nobody offered to refit the cockpit to meet Manchester's larger dimensions. Despite the discomfort, Rex handled the boat, outfitted all wrong for the taller, larger driver, as the Dame awaited Muncey's return.

Later in 1964, at Madison, Indiana, the Muncey-McDonald relationship fell apart. Once more Rex Manchester was offered the ride, this time with the promise of more permanence. He gladly accepted, recognizing the Notre Dame team to be everything his other unlimited experiences were not. The camp was fully equipped. The boat shop on Seattle's Aurora Avenue was the envy of the racing fraternity. The team had all the money it required to pay for every innovation desired. The boat was well designed, and there were more engines than Manchester had ever dreamed of having available. The only disappointment came when Jack Ramsey, whom Manchester respected as the very best, elected to resign as team manager.

Bill Muncey coached Manchester on the requirements of driving for Shirley McDonald. Muncey could not accept them. Manchester saw no difficulty in treating the boss as she desired to be treated. He did not possess Muncey's temperament, and getting along with a demanding owner was not difficult for Rex.

The few opportunities to drive the Notre Dame in competition in 1964 found Rex Manchester sharpening his skills and becoming familiar with the limitations of the boat. It was the best hull by far that Manchester had ever driven. The boat was responsive, forgiving and had power to burn! Though he did not post a win in 1964, Rex Manchester felt he had arrived. The year 1965 would be a great one for the "Shamrock Lady", and Rex Manchester believed he had at last reached the threshold of championship form.

Gene Mittlestadt photo

No unlimited hydroplane had ever been more thoroughly prepared to enter a season of competition than the Notre Dame was over the winter of 1964-65. The year was filled with expectation. Rex Manchester was hopeful and experiencing the happiest times of his life as a boat racer. He moved to Seattle to devote his energy to his position as team manager of the U-7 Racing Team. His wife Evelyn, daughter of oil-additive magnate Ole Bardahl, was his most ardent supporter, raising a family that was hog wild about unlimited racing. Rex's father-in-law was enjoying supremacy in the sport. His Miss Bardahl was brilliantly skippered by Manchester's closest friend Ron Musson.

Twice national champion and two-time winner of the Gold Cup, Ron Musson had achieved all that Manchester had wanted for himself. His friendship with Musson was legendary. Both were so much alike. Each had a quiet self-reliance and a confidence that required little reinforcement from their peers. Each appreciated the attention they received as competitors and sports figures, but neither sought the attention. Both preferred to escape that part of the experience. They shared a mutual respect for the talents each displayed. Musson believed that Manchester was destined to be one of racing's best drivers. He encouraged his friend. Manchester valued Musson's observations of his driving skills, and the two spent countless hours immersed in racing conversations before, during, and following each season. Like brothers, Manchester and Musson were close personal friends but fiercely competitive on the race course.

Rex Manchester knew that the late 1965 season would be a test of Ron Musson during a season in which Rex intended to be a winner at last, even at the expense of his friend. The two joked about fending off the other all through the tour. In fact, Musson often fended off the pursuing Notre Dame. Manchester drove well. The Dame ran impressively. Miss Bardahl just ran better. As it happened, so did an unexpected competitor, the Miss Exide. Hastily placed in service to replace the first Miss Exide in 1963, the former Wahoo had shown strong performances in 1964 with Bill Brow driving. Rex Manchester was impressed with the combination. He did not see the Exide as superior to his Notre Dame when the 1965 season began, but he quickly recognized that the season would not be just he and Ron Musson trading wins. Further, Chuck Thompson was having a strong year in the Tahoe Miss, and there were others showing staying power too.

The eastern swing of the circuit saw no wins for Notre Dame, although the boat was recognized as overdue for a string of first-place finishes. Manchester did not publicly display his displeasure, but he confided in Ron Musson that he was perplexed about why he had not been to the winner's circle. Musson was certain he would be before the season ended. In Seattle, preparing for the Gold Cup, Bill Brow drove Miss Exide to a world-record 120.356 m.p.h. qualifying speed for three laps. Musson piloted the Miss Bardahl to a hot qualifying speed, and Manchester kept the Notre Dame in the hunt with a respectable posting. Notre Dame was running better than ever. Manchester had more power than he had displayed. He wanted this Gold Cup. He felt he could win. Despite the formidable field, Manchester was convinced he could win.

The final Gold Cup heat saw Notre Dame most assuredly in winning form. In a couple of preliminary heat laps, Rex Manchester tested his friend and was confident that the Miss Bardahl could not outrun his boat. Ron Musson told Leo Van den Berg that he thought Manchester was ready to strike. He believed his friend was planning on taking the Gold Cup, and Musson felt he could have more than he could handle in the very impressive Notre Dame challenge. Vandenberg readied the Miss Bardahl in typical, professional fashion. He did not agree that the Dame was the boat to beat. He expected to have to outrun the powerful Miss Exide.

At the starting line, Leo Van Den Berg's prediction proved right. The Exide pulled the field into the first turn and began to draw away. Rex Manchester got the jump on his friend Musson and desperately chased the Exide Musson was surprised to be running third and could not close ground on the Notre Dame.

Bill Brow kept the Miss Exide solidly in first place, holding the Notre Dame a buoy's distance behind. Miss Bardahl found the power to close in on Rex Manchester, who by now was running as hard as he dared and could not catch the Exide. Out of the south turn on the second lap, a loud explosion resounded from the supercharger of the superior Miss Exide. Bill Brow knew his day was over and guided the red, white, and checkerboard Exide off the race course and into the infield. Rex Manchester could not believe his good fortune!

Looking back, he saw the charging Miss Bardahl gaining. He pressed the throttle to the wood, passed the disabled Exide, and pulled away from the pursuing Miss Bardahl in total command of the Gold Cup. Manchester's moment had arrived. He was three laps from winning at last! Rounding the south turn, Rex looked for the Bardahl By this time, Musson elected to lay back and hope for a miracle. The mighty "Green Dragon" had been outclassed. Ron Musson could not catch his friend. Although disappointed with himself, Musson was delighted that Rex Manchester was headed for a Gold Cup win. His first victory would be racing's sweetest!

As the Notre Dame streaked down the back chute on the third lap, Rex Manchester became alarmed at the intensity of the fire that had broken out aboard the Miss Exide He could see Bill Brow at the rear of the boat. The rescue helicopter hovered above, its litter hanging over Brow's head. The situation appeared serious. Brow might not be able to safely stay on the boat. If he went into the water before Manchester could finish, there would have to be a restart. Rex coaxed the "Shamrock Lady" onward, frequently checking on the blazing Miss Exide.

Ron Musson noticed the fire as well. For him, if the race were halted, his Miss Bardahl would receive a new chance to win the final. He privately hoped that Bill Brow could hold on for just another two laps. As Rex Manchester passed the official barge, ending lap four, the door slammed on his first trip to the winner's circle. Bill Brow, trying to hold on as long as possible, was forced to leap into Lake Washington. The Miss Exide was now fully involved, flames gutting this brilliant hydroplane. Flares greeted Manchester as he crossed the line. The Gold Cup final was being halted.

Back in the pits, Ron Musson tried to console his friend. Rex Manchester was accepting of the hand fate dealt him, but he was troubled by the irony of his incredibly poor luck. He thought of the many times he was so close and the many times he had been passed by. For some time, Manchester had been characterized by reporters as "Hard Luck Rex," and he was upset about how accurate that nickname was becoming.

The hour-long delay before the restart of the final heat was the longest hour in Manchester's career. He spent the time alone trying to prepare mentally for another shot at his best friend. When the final reconvened, Manchester was the first on the course. His concentration reached an intense peak as he keyed on Ron Musson. In the score-up, Manchester avoided Musson but kept watch. He knew he must have a perfect start.

Within thirty seconds of the start, Manchester shadowed the Miss Bardahl into the north turn. Both boats were wide. Notre Dame stayed to the outside of Bardahl. Manchester had elected to rely on what he thought to be Notre Dame's superior straightaway speed. He intended to outrun the Bardahl to the first turn in the open water.

The starting-line charge quickly became a mismatch. Rex Manchester calculated his start erroneously believing he could outpace the Bardahl. He trailed the "Green Dragon" into the first turn by several lengths. To further confound his situation, the Notre Dame's engine chose that moment to overheat. Apparently cooling water to the Merlin V-12 was being choked. The boat could not be driven hard, or the engine would let go.

Rex Manchester finished second in the 1965 Gold Cup. He watched his friend decorated as three-time Gold Cup champ in a bittersweet moment as the bridesmaid, again. In the fall of 1965, Rex Manchester informed Notre Dame owner Shirley McDonald that 1966 would be his last season as manager and driver of the Dame. His family was growing quickly; and Rex felt he had deprived himself and his children of a father, especially as he traveled during the season and had often to leave his family behind.

Nevertheless, Manchester intended to make his last season his best. Although the Notre Dame was picked as the heavy preseason favorite for 1966, Manchester discounted the media hype. He recognized that the Bardahl camp had invested in a radical, new, cabover, Ron Jones creation and that the concept had a lot of bugs. He knew that the powerful Miss Exide had been sold to Bernie Little and would campaign as the Miss Budweiser for a team that had never fielded a winner. He knew that Harrah's team had let Chuck Thompson go and had hired Mira Slovak to handle the Tahoe Miss. All of this pointed to an on-paper advantage for the Notre Dame camp, but Manchester was not convinced.

Still, he felt confident that the winter preparations had been thorough and that his boat was in top shape to be competitive. The hull had been stripped to the frame over the off season. Fully rebuilt, the Notre Dame was now about 600 pounds lighter. Significant prop work had been performed over the winter, and the team had acquired some very fine propellers. Sponson work performed promised to permit the Dame to corner better than ever.

The Notre Dame tested early and often in the spring of 1966. Even before her familiar color scheme had been painted on her new deck, the all-white Notre Dame had been in the water testing hull refinements. The boat was ready. Manchester was ready. Rex was able to put the past behind him. He looked to the season opener at Tampa to prove the worth of all the hard, winter shop work.

Manchester tried not to think about the '65 season. He did not want to dwell on Roy Duby's steering error that nearly cost him his life at Lake Tahoe in September. He did not want to ponder the Gold Cup or how he had miscalculated the strength of a number of boats that beat him that year. He wanted only to win, at least once, before he retired at the end of the year.

The 1966 Suncoast Cup got off to a bad start. Hurricane Alma, early for the season and unexpected, wreaked havoc with the Tampa race course, disrupting qualifying and permitting only two days of pre-race testing. As it became clear that there would be insufficient time to allow all boats present to qualify before race time, officials bent the rules and admitted any boat that had previously qualified for an APBA unlimited event.

While convenient, the lax qualifying ruling prevented Rex Manchester from testing the Notre Dame thoroughly on the Tampa Bay course. Worse, it prevented him from seeing what the others had to offer. Rex was especially interested in how the new magnesium Miss U.S. would perform with Bill Muncey at the wheel. He also wanted to look over the Smirnoff, which, rumor held, had a very impressive preseason testing period in Detroit.

Miss Bardahl experienced gearbox troubles, and Manchester's friend Ron Musson stood by while his new boat was withdrawn in Tampa. The rough water caught the Smirnoff in a hole, inflicting minor injuries on Bill Cantrell. Miss Budweiser hooked violently, causing a nasty shoulder injury to Bill Brow. Rex Manchester survived the battering and squared off with Bill Muncey in the day's final. Muncey enjoyed a point lead, and even though Manchester outperformed Muncey in the final, the Miss U.S. won in Tampa on the basis of points. Again, Rex Manchester was forced to settle for second place.

Gary Todd photo

Notre Dame looked impressive in Tampa. Washington, D.C. was expected to separate the seasoned Dame from the rest of the fleet. Preseason predictions still held the Notre Dame out as boat to beat. In Washington, Rex Manchester enjoyed pre-race media attention usually reserved for the leading boat in the fleet.

The weather and water conditions in the nation's capital were as cooperative as anyone had ever known them to be. The two-day President's Cup event saw a Saturday slate with the first section of heats on the schedule. Rex Manchester handled the Notre Dame in typical, professional fashion, winning his first stanza. He then watched while Ron Musson displayed his trademark grit holding off challenges and guiding the new Miss Bardahl to its first heat victory.

With wives back home in Seattle, Rex Manchester and Ron Musson spent after-hours time talking boat racing. Musson complained of difficulty feeling his new Miss Bardahl. He spoke of not being comfortable with the boat at speed since his test program had been relatively brief as mechanical troubles kept the boat from a lengthy Lake Washington test series as originally planned. Musson and Manchester looked to the next day of racing. Musson believed that the time was right for Rex to finally tally his first win. Rex reservedly agreed and told his friend that he really wanted this one.

Sunday, June 19th, the two close friends were drawn together in the second round of heats. They enjoyed racing each other. Each knew the other's moves. Each trusted the other's competence. They liked to go fast when racing each other. Manchester hoped that Musson could. The fragile Miss Bardahl had not seen much high-speed action.

In their heat, the Notre Dame and the Bardahl got a picture-perfect start. The two friends raced aggressively, trading the lead several times, always within a boat length. At the end of the back chute, after a splendid first-lap duel, the Miss Bardahl lost her advantage, visibly handling poorly. Manchester, on the inside, drew alongside. The two boats exited the turn abreast, and as the Notre Dame lunged ahead by a length, the Miss Bardahl appeared to take a wild leap and then another, gyrating as she porpoised. The Bardahl's nose disappeared beneath the water's surface, and within a second, the boat erupted in a blast of spray and debris from which the aft portion of the hull was seen hurtling down the front chute with the engine attached.

Rex Manchester had pulled away, and not seeing Musson beside him as he entered the turn, he started up the back chute and noticed the accident scene. Cutting the course as the flares shot skyward, Rex Manchester knew instinctively that something awful had happened to his friend. Rescuers had pulled the stricken Musson from the Potomac. Manchester could do nothing for his best friend now. He registered solemn concern for Ron Musson as he stepped from the Notre Dame and rushed to the stunned Bardahl camp to be with his father-in-law and his friend.

Although no announcement had been officially made, Rex Manchester knew that Ron Musson had not survived. He saw the rescue boat bring Musson to shore. He knew the severity of his friend's injuries. He had conferred briefly with Ole Bardahl before the latter accompanied his driver to the hospital. What Manchester could not have known was that he was living the final hours of his life.

Following a brief conference of drivers, who voted not to cancel the President's Cup, Manchester participated in the restart of the heat wherein his friend Ron Musson had been so seriously injured. Manchester believed Ron Musson was dead. His premonition was confirmed a short time later. He telephone his wife and instructed her to drive across town to be with Betty Musson, who was soon to hear the painful news of her husband's tragic death. Evelyn Manchester complied without the slightest inkling that she had spoken to Rex for the last time.

Although he knew in advance of the public-address announcement, the news of Ron Musson's death, now confirmed publicly, caused Rex Manchester a great deal of trauma. Drivers again voted to continue, believing that Ron Musson would have wanted it thus. Rex Manchester accepted that notion, and mechanically he prepared to drive the final. The Notre Dame and the Miss Budweiser, driven in relief by Miami's Don Wilson, were close on points. Manchester would have to win the final to secure the President's Cup.

Rex Manchester pulled out onto the course before any other boats. He drove several laps alone before being joined by the remaining finalists. Some have suggested that the Notre Dame would have had not nearly enough fuel to complete the final after as many preheat laps as Manchester posted while thinking alone in the cockpit of his boat. Don Wilson was visibly upset about the death of Musson. Like Manchester, Wilson was a close friend of the fallen Bardahl driver. He had helped Musson post his first national title, and co-drove the "Green Dragon" in 1963. He was stunned at the news of Musson's death. Emotional, and perhaps unfit to race, Wilson climbed into the Miss Budweiser cockpit and roared out onto the course.

On shore, anxious crews and officials watched the final-heat field score up. More than one observer felt that this heat should not be run. Rex Manchester steered the Notre Dame to an outside slot as the boats rounded the turn to head for the line. Miss Chrysler Crew took the inside with both the Budweiser and the Dame back a few lengths. As the seconds ticked down, the familiar roar of the massive Rolls engines in both the Miss Budweiser and the Notre Dame filled the capital. Into the first turn, Bill Sterett held the lead. Miss Chrysler Crew was suddenly passed as if she were at anchor. Out of the corner, Don Wilson throttled the Miss Budweiser into the lead and moved to the inside track. Notre Dame was a length back, her profile visible in the Bud's spray.

At the midway point of the stretch, Rex Manchester blasted the Notre Dame into the lead with a spurt of speed that was answered in a second by Miss Budweiser. Some observers on the beach grew nervous. To them, it appeared that the boats were going too fast by the time they reached the end of the chute.

With little more than a length's lead and riding on the outside at a pace that now had everyone apprehensive, Rex Manchester appeared to set the Notre Dame to enter the turn. The boat took a long leap at least three feet off of the water. Notre Dame touched down then leaped again, wrenching to the left while skidding on her right nontrip. In a flash, the boat was in the path of the charging Miss Budweiser. There was scarcely a moment to comprehend the peril when both boats erupted in an explosion of immense finality.

The instant seemed to last in a surrealistic display as Notre Dame's cowl floated through the spray high above the crash, and the sprawling body of Don Wilson cartwheeled down range from the explosion -- an unbelievable sight. On shore, there was stunned silence. No one moved. So unlike any racing accident they had ever seen, this one had shocked onlookers, who stood paralyzed by the spectacle.

Rescuers seemed annoyingly slow to respond. It did not matter. Both drivers were beyond hope. Records show each died instantly. There were no indications that water was inhaled. Medical examiners say the crash took them in an instant. Rex Manchester's body was recovered from the cockpit of the Notre Dame as the wrecked hull bobbed nose down in the churning Potomac.

This time officials called for no drivers conference. The final heat of the 1966 President's Cup was cancelled. The points were totaled, and the incongruous realization came that Rex Manchester had won the regatta. In his passing, Manchester achieved what he could not accomplish while living. He had become, at last, a winner.

On June 24, 1966, beside his friend Ron Musson, "Hard Luck Rex" was laid to rest in Seattle. In the archives of unlimited hydroplane racing, achievements are logged revealing the race-course exploits of the sport's greatest drivers. Rex Manchester is not found among the top-ranked drivers. His single race win is not statistically important. He will be overlooked by those who open the record book to see who was best. The record book does not contain his ironic story.

At the time of Manchester's passing, a popular tune on the charts accurately described the racing career of this fine competitor: "The race is on, and it looks like heartache ... the winner loses all."

(Reprinted from the Unlimited NewsJournal, March and April 1991)