Steve Reynolds

The Steve Reynolds Story

By Fred Farley - Unlimited Hydroplane Historian

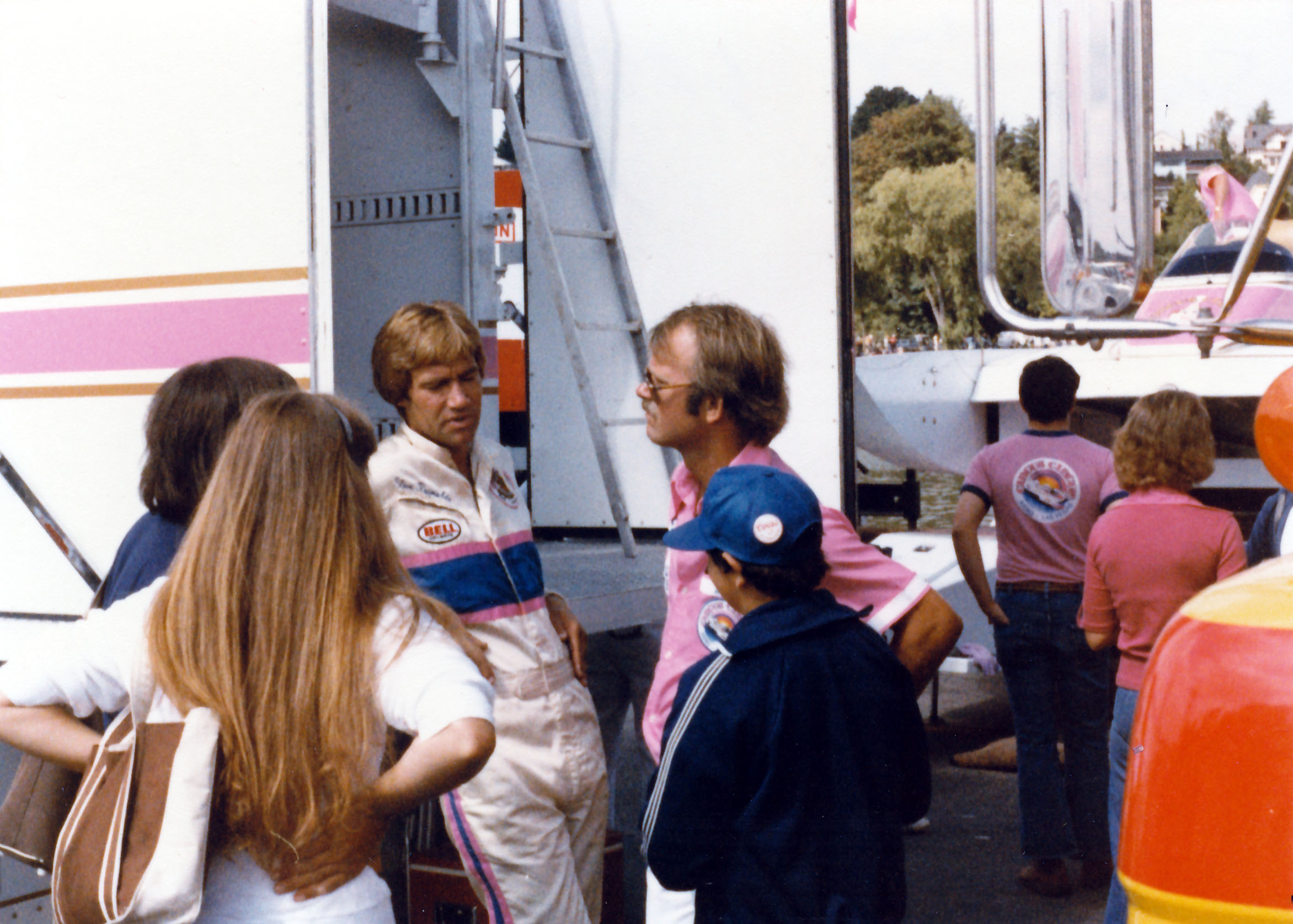

There was a bright new star on the Unlimited hydroplane horizon in 1979. He was Steve Reynolds, driver of the casino-sponsored Miss Circus Circus.

Reynolds had just completed his first full season with the world's most spectacular racing boats. The Kirkland, Washington rookie shaped up as the most exciting new talent to occupy a Thunderboat cockpit in many a moon.

At age 32, Steve had command of second-place in a field of twenty drivers in accumulated season points.

He had qualified fastest at four out of nine U-boat events, set a world record with a 2.5-mile lap speed of 133.136 miles per hour at the Tri-Cities Columbia Cup, was the Unlimited Class Rookie-of-the-Year, and the proud owner of the Jack-In-The-Box Thunderboat Regatta first-place trophy for a winning performance on San Diego's Mission Bay.

A former U.S. Marine helicopter crew chief and gunner during the Vietnam War, Reynolds posted a 1979 competition box score of 24 heats started, 21 finished, nine in first-place, six in second, five in third, and one in fourth, piloting the pink-and-white-colored U-31.

In addition to the San Diego victory, Reynolds took second-place in the nationally televised APBA Gold Cup Regatta on the Ohio River in Madison, Indiana.

Steve began his racing career in the early 1970s, shortly after his return from Southeast Asia.

The first boat he ever raced was a conventional 225 Cubic Inch Class hydroplane called the Sundance Kid. It wasn’t exactly a world-beater, but it was a start in the sport that he loved and the first step toward eventually driving an Unlimited. Steve didn’t win any trophies with the Sundance Kid, but he gained a lot of experience.

The logical next step for Reynolds was a more competitive hull. But that would take time and money. According to Steve, "I sat out a year and sold everything I owned. I moved back in with my folks so I wouldn’t have to pay rent, and drove one of my Dad’s trucks. Every dime that I made I turned over to my Mother, who made sure that all of my bills were paid. Everything else went in the bank.

"I contacted Ron Jones and would have bought one of his hulls but I had to wait about seven or eight months before he could start construction. Then I ran into Dave Knowlen, who had heard that I’d been looking for a boat. He laid out a set of 225 blueprints on the hood of a truck, then took me to the shop of a builder named Norm Berg. I looked at some of Norm’s craftsmanship and said, 'My gosh, that’s every bit as good as Ron Jones." He replied, "Well, I worked for Ron for eleven years.'"

They finally agreed on a price, and Norm began construction. This was about a year and a half after Steve had made a commitment to get a new hull, which became the White Lightning--a white and blue cabover with a Buick engine, prepared by Bill Grader. White Lightning (later sponsored by Pay ‘N Pak) was the first to use a horizontal stabilizer wing in the 225 Class.

The boat was a front-runner right out of the box and for two years was the dominant 225 on the West Coast. It set two competition heat records for the 225 Class: 97.930 in 1976 and 98.850 in 1977.

One of Steve's fondest memories is his second-place finish to Jim Kropfeld and Country Boy at the 1975 Inboard Nationals on Seattle's Green Lake.

"Jim is a good friend of mine. We ran one-on-one for two and a half laps in probably the finest heat I have ever driven. It was racing at its very best. I was hanging in the air and so was he. Neither one of us took our foot off the floor for three solid laps."

Steve experienced some of his happiest boat racing moments when he was campaigning White Lightning. At the Lake Sammamish Limited races, Reynolds and his crew and their families would enjoy a picnic lunch in the pits.

"In the beginning, I didn’t even have a crew. It was just my Father and me. I knew that I couldn’t drive and crew at the same time if I wanted to concentrate on my ultimate goal of driving an Unlimited hydroplane. I needed a crew chief, and I found an excellent one in Jim Harvey, who had been with Miss Budweiser. Jim went on, in 1978, to become Crew Chief for Miss Circus Circus, my first Unlimited ride and the fulfillment of a lifetime wish."

The owners of Miss Circus Circus, Mr. William G. Bennett and Mr. William N. Pennington, put together as much talent that was available in the field. They hired the core group of the highly successful White Lightning team: Reynolds, Harvey, Knowlen, and Berg. Also included was E.B. "Tiger" Reynolds, Steve's father.

On September 17, 1978, the team took third-place at San Diego with the original Miss Circus Circus, which had run in 1977 as Bernie Little's Anheuser-Busch Natural Light. The team was less than three weeks old. It was Steve's first race of any kind since an accident with his 225 at Seattle's Green Lake in May of that year.

"We were happy with our initial performance, although that was to be the first and last time that we would ever be satisfied with anything less than first-place."

The crew had their backs up against the wall as they prepared for 1979, knowing that they had to do in six months what ordinarily takes a year. Their work was plainly cut out for them. Not since 1966 had a new team with a new boat and a new driver been able to win an Unlimited race in its first season.

But according to Steve, "This was the kind of challenge that brought out the best in Jim Harvey--the one veteran in the group--in his first assignment as a Crew Chief."

Finding suitable engines was also a challenge. By the late 1970s, Rolls-Royce Merlin engines were becoming scarce.

"We really had to dig the Rolls-Royce Merlins out of the woodwork. Some of the engines that we acquired came from all corners of the Earth--in South America, Australia, New Zealand, India, and Europe."

The new Miss Circus Circus was launched on April 26, 1979, on Lake Washington in Seattle. Christened by Nevada Governor Robert List, the craft measured 29 feet by 13 feet 10 inches and tipped the scales at just over 6,000 pounds.

As a youngster, Steve had always been a fan of the famed "Pink Lady" Hawaii Kai III, winner of the 1958 Gold Cup Race in Seattle with Jack Regas driving.

"We painted our boat pink as well--three shades of it--on white with gold and black trim. At the christening ceremony, my wife Linda had our baby daughter Krista decked out in a new pink jumpsuit, embroidered with the logo 'Pink Team.'"

Heading into the first race of the season in Miami, Steve was apprehensive. They really didn't know what the boat was going to do at top speed with other boats running with it.

In Miami, the boat had a serious hooking problem although it did manage to qualify fastest at 120.000 around the 2.5-mile course and at 110.092--a record--on the 1.67-mile course.

"We took second-place overall behind Bill Muncey and the Atlas Van Lines, and I won my first heat there in Section 2-A. As I look back on the experience, several things needed to be established right off the bat: Number one, that the Miss Circus Circus was going to be a contender all year long; and number two, I wanted to gain the respect, as a driver, of the other drivers.

"I made three very good starts at Miami, and we actually led at one time or another in each heat. So, we were pleased."

Then, it was on to Evansville, Indiana, where Miss Circus Circus didn't finish in Heat One when the Nitrous Oxide valve stuck open. For the second heat, Reynolds decided that he would have to get Muncey and Atlas Van Lines out of position and tried to keep Bill "on his hip" all the way around the corner, coming around for the start.

"I kept him there until he began to slide to the inside of me. When I saw that, I moved over to lane-one, and I was on my way to the checkered flag. I thought it was a pretty good move, because it certainly paid off for us. We averaged 111.975 to Muncey's 111.317 for five laps around the 2-mile Ohio River course."

The Circus team finished an overall second to the Atlas at Evansville, but not without a near-collision with Muncey on the upper turn of the first lap in Heat Three. Bill was running ahead of Steve on the outside and apparently didn't know that Reynolds was there.

"I watched the back of his helmet all the way down the back chute. And as I was picking up on him, I was saying, 'God, Bill, will you please turn around and look and see that I'm here?' And it came to that moment of decision: Do I back out of it and go through his roostertail, or do I stay in it and hope that he leaves me enough room. And, in that second of indecision, I was already committed. I turned the boat as hard as I could and went right up over the top of his skidfin.

"The boat went over his cowlings. The guys in the pits thought that the boat was gone. I just ducked my head down and waited for the crunch. I'm surprised that it came down right-side up and kept on going. I talked to Bill about it later. It was an interesting conversation."

At Detroit, the team had its first major problem with propellers. Throughout the year, Miss Circus Circus had an extraordinarily good record with engines. They didn't lose any due to engine failure per se. They did scatter a couple of them as a result of losing the propeller and the power plant over-speeding.

"Jim Harvey and I worked on and had a lot of conversations about engines. You don't just drive these boats. You have to drive those motors as well."

Steve had a near-miss with a wall as he came out of the infamous "Roostertail Turn" on the first lap of the Detroit race. The incident would become a part of hydroplane lore.

During the Second Heat warm-up period, Muncey grabbed the inside lane going down the back chute. Steve hid right in his blind spot, where Bill couldn't see him. And, just at the time that they entered the corner, Reynolds cut across the transom of the Atlas, tucked right alongside of Muncey, looked him right in the face, and said, "Hey! Here I am!"

"When he sped up, I would speed up; when he slowed down, I would slow down. I just would not let him get on the inside and ahead of me. When we started to set up on the buoy, I went about two lanes deeper into the corner. So, he had to correct to the right. And the moment that I saw him turn his hands to the right, I turned to the left and picked up about three boat lengths on him.

"I had, I thought, a pretty good lead when I came out of the corner, but then the boat stopped dead in the water. I figured that we had just lost the front end when in fact the propeller had let go. The blower had really scattered. There was no gear box, no prop shaft, and about a seven-foot hole in the bottom."

Back in the pits, there didn't seem to be any way that the boat could be ready for the Gold Cup Race the following week in Madison, Indiana. But after a round the clock repair effort, it was.

Although he finished the day at the end of a tow rope, Detroit proved to be an important milestone for Steve Reynolds in his development as an Unlimited driver.

"I had challenged Muncey and beaten him. Bill may have won the Spirit of Detroit Trophy, but a driver is only the best from week to week. And I let Muncey know that I would keep coming at him until it was me who would win the first-place trophy."

The crew made some modifications to the boat at Madison and it seemed to be running better. However, it was still getting dangerously loose at about 155 miles per hour. The faster it went, the higher Miss Circus Circus flew out of the water.

Reynolds won all three of his elimination heats at Madison and managed to beat the Atlas in Section 2-B, setting a course record of 113.636 for the 15-mile distance.

Going into the Championship Heat, the Ohio River was rough, but--judging by the competition of the day--Steve was optimistic. He led into the first turn and then hit a turbulent stretch.

"My boat did everything but flip. I saw that well known 'blue blur'--the Atlas Van Lines--roar past me and Bill Muncey was on his way to the bank once again. We took second ahead of Chip Hanauer in The Squire Shop."

Steve was quite disappointed, but his crew gave him a round of applause when he returned to the dock.

In an attempt to calm the boat down for the next race in El Dorado, Kansas, Dave Knowlen designed a spoiler. It helped a great deal and enabled Miss Circus Circus to qualify fastest at 126.316 around the 2-mile course on Lake Bluestem.

The boat was now being regarded as a bona fide contender but it was still having problems. During the qualification period, it broke two skid fins.

"Nothing that I can think of--and this includes my Vietnam experience--worries me more than going into a turn at 165 miles an hour and losing a fin. This happened at El Dorado. I have no idea how I stayed with the boat. It rolled up on its right side two or three times before it swapped ends and stopped. I was only hanging on by one hand. My right hand was on the wheel, and my left foot was up in the air."

Reynolds won the first heat and took third in the second at El Dorado but had a problem with the Nitrous Oxide in the Final.

"It was all inexperience on my part. I didn't have enough RPM on the engine, and I hit the Nitrous button too soon. When that happened, the Nitrous plus the fuel flooded the engine and the spark plugs fouled. It was just a rookie mistake, and I learned the hard way. But that was the first race of the season where we had gone in as the favorite."

Moving out West to the Columbia Cup at the Tri-Cities, Washington, Steve felt truly comfortable with the boat for the first time. He felt in control.

Miss Circus Circus qualified at the fastest speed ever turned on a closed course up until that time: 133.136 miles per hour. They had damaged two engines that week because of induction temperature problems. When he went out for the record run, Jim Harvey told him, "If it feels good, go ahead and give it one or two really hard laps, but don't break anything."

Reynolds won his first Columbia Cup heat at 121.033 miles per hour. The next time out, he was trailing Dean Chenoweth and the new Rolls-Royce Griffon-powered miss the Budweiser by a few seconds and leading the Atlas Van Lines when Miss Circus Circus broke another prop. This necessitated another rebuild job for the following race in Seattle.

In the Final Heat at Seattle, Steve thought he had the Seafair race won before the hometown crowd, until he realized that he had jumped the gun. He did so by less than a boat length, but that dropped him to an official fourth-place overall.

"I was terribly disappointed and angry, but I nevertheless stayed ahead of the field and didn't let anyone pass me. It was a case of Steve Reynolds paying his dues. In the meantime, Muncey recovered from a bad start and eventually outran Chenoweth to win the race."

The next race in Ogden, Utah, was one that Steve would like to forget. The team had nothing but trouble. They ran the boat ten or eleven times during the week but couldn't get it to run properly.

After running second in Heat One, the propeller let go again and really caused a lot of damage. It didn't look as bad as Detroit, but it was harder to fix. Both main engine stringers were broken, together with a lot of frames and hardware, including the steering gear. They also bent the rudder and the transom blew out.

It was eight down and one race to go on the 1979 schedule. Steve had proven his competitiveness. But he still had not won a race.

"I've been asked if the reason I seek victory is for the thrill of winning or the fear of losing. After the 1979 race in San Diego, I can say that it's DEFINITELY the thrill of winning...and win we did in the last race of the season on Mission Bay, where the team first appeared the year before."

Going into the Final Heat at San Diego, they gambled on an untried propeller. Jim Harvey was worried about blowing an engine, and Dave Knowlen didn't know what the new prop would do. The owners, Mr. Bennett and Mr. Pennington, wanted to go with the newer wheel. So, the die was cast.

The attrition was fierce at San Diego. Atlas Van Lines dropped out and so did Miss Budweiser. Coming out of the first turn, The Squire Shop and Miss Circus Circus were side by side.

Hanauer wanted to slide wide, but Reynolds wouldn't let him. The Circus pulled away from the Squire and was never headed. Steve took the checkered flag and won by a wide margin.

"I've never been so excited in my life. I beat the hell out of the steering wheel, jumped up and down, and waved my arms, while still going 150 miles an hour. It about sucked me out of the cockpit.

"Returning to the pits, I felt like MacArthur coming back to the United States. The Navy Band was there, playing the theme from Rocky. People were squirting champagne up in the air. I mean everybody was thrilled. That was just a tremendous day. And it was the greatest thing that happened to me all year. I'll never forget that feeling."

Steve Reynolds, Jim Harvey, Dave Knowlen, and the Miss Circus Circus team had--in the space of a year--proven their mettle in championship fashion.

Rookie-of-the-Year Reynolds would win other races in other seasons. But 1979 would be his most memorable--and most satisfying--campaign. He had realized his lifelong dream.

Steve stayed with Miss Circus Circus for another year. But 1980 was not a happy experience for Reynolds, despite finishing third in National High Points.

Owner Bill Bennett made personnel changes in 1980 that didn't help the team. He fired or demoted to secondary status most of the 1979 crew that had worked together so well, most notably Crew Chief Jim Harvey. Many of the crew members that started the 1980 campaign weren't there at the end of the season.

The Miss Circus Circus experience ended on a sour note for Reynolds. The team was headed in a direction that Steve did not approve. (For 1981, Bennett and Pennington sold the 1979 hull and concentrated instead on an experimental four-pointer that failed as a competitor and was an embarrassment to the sport.)

Reynolds saw brief action with Captran Resorts in 1981 and with Miss Prodelco and Gilmore Special in 1982. He won a secondary race at Seattle with Captran and took second at Evansville with Prodelco.

Steve's career shifted back into high gear in 1984 when he signed with Steve Woomer's Competition Specialties team. This was a top-of-the-line organization with quality personnel, including the likes of Jerry Verheul and Jim Lucero as crew chiefs. This was one of the first teams to recognize the potential of Lycoming turbine power.

Reynolds took first-place in the UIM World Championship Race at Houston, Texas, under the sponsorship of Miss Tosti Asti. Steve averaged 121.534 in the Final Heat, compared to 114.448 for Ron Snyder in American Speedy Printing/Miss Madison and 111.448 for Mickey Remund in The Squire Shop.

Steve won another big one the following year in the Indiana Governor's Cup at Madison with Woomer's Miss 7-Eleven. Heading into the Final Heat, a showdown shaped up between Reynolds and his old friend Jim Kropfeld, driving the Rolls-Royce Griffon-powered Miss Budweiser.

Reporter Denny Jackson described the action as follows in the Unlimited NewsJournal:

"The first lap of the Final was indeed a classic battle between the turbine and the piston engine. Reynolds couldn't shake Kropfeld on lap-one as he averaged 123.253 to Jim's speed of 121.375. The race put on a new face after that as Reynolds pulled away from Kropfeld and the rest of the field.

"The Bud began to settle for second when his oil pressure dropped causing the engine to blow. Kropfeld was now reduced to a spectator. At the finish it was Reynolds and 7-Eleven taking home the first Madison win in his career with an average speed of 118.137."

Prior to the 1986 campaign, Miss 7-Eleven's cockpit was equipped with a completely enclosed F-16 fighter plane safety canopy.

During a post-season test run on the Columbia River at the Tri-Cities, the skidfin broke at 155 miles per hour. Miss 7-Eleven did an inside roll, landed upside down, and flipped right-side up again. Back on shore a few minutes later, Reynolds, who suffered only minor bruises, told his crew, "There's no question that the canopy saved my life. If it weren't for that canopy, you guys would be looking for my head."

The APBA Unlimited Racing Commission was quick to recognize the value of the F-16 canopy. Starting in 1987, all new boats were required to use the canopy. Older boats were given until 1989 to make the change-over.

The 1986 season proved a disappointment to Steve--even though he and Miss 7-Eleven finished third in National High Points. The team placed second at Syracuse and third at Evansville, the Tri-Cities, and Seattle. But Reynolds was, after all, out there to win.

A new sponsor--Cellular One--came on board for 1987. The boat was rebuilt during the off-season by Crew Chief Lucero. It entered competition virtually untested. At the early season races, the boat had a problem with stability.

Despite a strong second-place finish at Evansville, Cellular One was "floating" much higher than usual. This tendency was to spell disaster for the team a week later at Madison and the end of Steve Reynolds' racing career.

After finishing second and first in preliminary heat action, Steve was leading down the first backstretch of Heat 3-A, ahead of second-place Kropfeld and Miss Budweiser. As he neared the Milton-Madison Bridge, Cellular One became airborne, blew over backwards in a violent snap roll, and crashed.

The boat--what was left of it--landed upright. Reynolds was found unconscious and critically injured. The recently-mandated F-16 safety canopy was credited with saving Steve's life.

His daughter Krista witnessed the crash.

Reynolds spent several weeks at Indianapolis Methodist Hospital recovering from head trauma and other injuries. He was later transferred to a Seattle facility before being released.

The seriousness of Steve's misfortune has been compared to Jack Regas' accident with Miss Bardahl at Coeur d'Alene, Idaho, in 1959, and to John Walters' horrendous crash with Pay ‘N Pak at Seattle in 1982.

Reynolds' driving days were over.

"If I took a hard hit on the head, I'd wind up in the hospital again as a vegetable or a quadriplegic, or worse yet, I'd wind up dead."

It was a sad farewell indeed for one of racing's most popular and fan-friendly personalities.

In the years since his accident, Steve has remained a familiar figure on the Unlimited hydroplane circuit.

Never too busy to sign an autograph or to pose for a photograph, he was, he is, he always will be, the stuff that heroes are made of.

Between 1978 and 1987, Steve Reynolds participated in 60 Unlimited races and finished in the top-three at 24 of them. He was first three times, second 1.